Poltico: NIZHNY TAGIL—Felix Nikolaevich Kolsky knows war. His grandfather had five sons, and only one came back from World War II. Kolsky’s father was one of the ones who didn’t make it home, and Felix was born in his absence, shortly after he went off to the front in 1941. “My generation never recovered,” he says of the 27 million people the Soviet Union lost in the fight, “so there is just no way that we want another war.”

Poltico: NIZHNY TAGIL—Felix Nikolaevich Kolsky knows war. His grandfather had five sons, and only one came back from World War II. Kolsky’s father was one of the ones who didn’t make it home, and Felix was born in his absence, shortly after he went off to the front in 1941. “My generation never recovered,” he says of the 27 million people the Soviet Union lost in the fight, “so there is just no way that we want another war.”

And so, to help Russia avoid another catastrophic conflict, he decided to do something about it: He wrote to Donald Trump.

“Dear Mister Donald Trump,” he wrote. “Greetings from the most ordinary Russian citizen, Felix Nikolaevich Kolsky.” From his home in this blighted industrial city on the eastern slope of the Ural Mountains, Kolsky says he has been following the U.S. Presidential election and has concluded one thing: “From the group of candidates for the presidency, you are the only one who inspires confidence,” he wrote to Trump. “When you followed your father’s footsteps into the construction business, you were very successful; you increased your family’s wealth many, many times over.” Kolsky sees in Trump an American Everyman. “Your work in this field creates a convincing image: a laborer into whose reliable hands we can entrust the fate of the [American] people and country.”

But, again, Kolsky is really a one-issue voter—were he able to vote in the American elections all. He doesn’t want war with America, and Trump doesn’t seem to want to go to war with Russia. “You are the only candidate for president who doesn’t use rhetoric about the military threat from Russia,” Kolsky wrote. “Possessing superior military potential and [the most] developed economy in the world, you are always able to resolve the most pressing problems peacefully. Your phrase from March 22, 2016: ‘It is much better to build relationships with all governments, but it’s always better to get along with them.’ ‘If if we get along with Russia, that would be great.’”

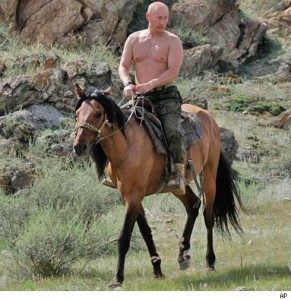

Russia and America haven’t been getting along for a while now. Ever since President Barack Obama’s “reset” fizzled and Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, relations between the two countries have sunk to what pundits like to call “Cold War lows.” But suddenly, unexpectedly, this election has presented the Kremlin and Russians with a champion—a man who openly says he would get along with Putin, who would build a relationship with him and with Russia, and would pull America off the world stage, where it keeps getting tangled in Russia’s feet.

Trump’s warm comments about Putin have horrified American foreign-policy stalwarts and become an issue on the campaign trail. Trump has praised Putin; Putin responded by calling  him “talented” and “colorful.” Hillary Clinton seized on this in her recent foreign policy speech, mocking Trump for saying that, “if he were grading Vladimir Putin as a leader, he’d give him an A.” She added, “If you don’t know exactly who you’re dealing with, men like Putin will eat your lunch.” But if many Americans are anxious and the rest of the world scared of a potentially destabilizing Trump presidency, Russia is salivating at the prospect: Trump seems to understand Russia’s might and wants to get out of Russia’s way. There’s also something Russian about Trump the man: he likes gold-plated opulence and surgically-perfected Eastern European women; he eschews political correctness and shoots from the hip. He is a man they can understand, and who, they hope, will understand and respect them—a rarity for an American president.

him “talented” and “colorful.” Hillary Clinton seized on this in her recent foreign policy speech, mocking Trump for saying that, “if he were grading Vladimir Putin as a leader, he’d give him an A.” She added, “If you don’t know exactly who you’re dealing with, men like Putin will eat your lunch.” But if many Americans are anxious and the rest of the world scared of a potentially destabilizing Trump presidency, Russia is salivating at the prospect: Trump seems to understand Russia’s might and wants to get out of Russia’s way. There’s also something Russian about Trump the man: he likes gold-plated opulence and surgically-perfected Eastern European women; he eschews political correctness and shoots from the hip. He is a man they can understand, and who, they hope, will understand and respect them—a rarity for an American president.

Kolsky is hoping for an American president who doesn’t treat Russia as an enemy, and for a return to an earlier (possibly illusory) friendship between the two countries. In his letter, he explains that, despite America spending far too much money on NATO to shelter the provocative, anti-Russian Baltics, Russia and America are natural, historic allies. The U.S. provided critical help to the Soviet Union during World War II with the Lend-Lease program, which, perhaps was just America returning the favor. “In the Civil War of 1861-1865 between the North and the South … Russia, with the agreement of the government of Abraham Lincoln, brought in one naval squadron into the port of San Francisco, and another into New York harbor,” Kolsky writes. “This precluded the possibility of military intervention of England and France … It was serious moral support.” (This story is also seriously dubious—the Russian fleet wasn’t really there to support the Union, though it apparently greatly boosted Union morale—but speaks to a certain very American trait among Russians: thinking they’re at the pivot of world events.)

return to an earlier (possibly illusory) friendship between the two countries. In his letter, he explains that, despite America spending far too much money on NATO to shelter the provocative, anti-Russian Baltics, Russia and America are natural, historic allies. The U.S. provided critical help to the Soviet Union during World War II with the Lend-Lease program, which, perhaps was just America returning the favor. “In the Civil War of 1861-1865 between the North and the South … Russia, with the agreement of the government of Abraham Lincoln, brought in one naval squadron into the port of San Francisco, and another into New York harbor,” Kolsky writes. “This precluded the possibility of military intervention of England and France … It was serious moral support.” (This story is also seriously dubious—the Russian fleet wasn’t really there to support the Union, though it apparently greatly boosted Union morale—but speaks to a certain very American trait among Russians: thinking they’re at the pivot of world events.)

“Given the situation in the world today,” Kolsky concludes, “we need knowledgeable, calm politicians with sturdy characters who are capable of peacefully resolving every pressing issue. Donald Trump can be this man. I hope that the American people will elect Donald Trump president of the USA. I’m ready to contribute financially to Donald Trump’s election campaign fund in the sum of 100,000 rubles. I hope that American society will understand my position. I don’t want my Russians to suffer the fate of the 27 million Soviet citizens who died in the Second World War.”

“Given the situation in the world today,” Kolsky concludes, “we need knowledgeable, calm politicians with sturdy characters who are capable of peacefully resolving every pressing issue. Donald Trump can be this man. I hope that the American people will elect Donald Trump president of the USA. I’m ready to contribute financially to Donald Trump’s election campaign fund in the sum of 100,000 rubles. I hope that American society will understand my position. I don’t want my Russians to suffer the fate of the 27 million Soviet citizens who died in the Second World War.”

He then printed out the letter and gave it to his 19-year-old granddaughter Katya, who translated it as best she could, and then traveled for two hours to the nearest American consulate in Yekaterinburg to mail the letter. “If you send it through the Russian mail,” she told me of the notoriously dysfunctional national mail service, “it probably won’t ever get there!” She also caught some flak for going there at all. “My friends said, ‘Why are you going there? They are our enemies!’” Katya shrugged. “Yes, the news are terrible,” she said. “But conflicts come and go.”

* * *

Kolsky is, in many ways, quite ordinary, and, like his image of Trump, a laborer. Seventy-five years old, he spent four decades in the sweltering belly of the city’s famous metallurgical plant, making giant sheets of steel that formed the bottoms of train cars. The plant, like Russian manufacturing sector as a whole, has since fallen on hard times. It churns out far fewer train cars than it used to, salaries have been slashed, its workers (including two of Kolsky’s sons) have been switched to a four-day workweek, and rumors swirl of mass layoffs. Food prices have grown by double digits. Locals grumble about non-Slavs running the cafés in town.

In other words, it would be Trump country if it weren’t the very heart of Putin country.

During Putin’s reelection campaign in the winter of 2011-2012, liberal Muscovites turned out en masse to protest his return to the Kremlin for a third term. The workers of Nizhny Tagil, on the other hand, went on national television and said they were ready and willing to come to Moscow and beat up the protesters on Putin’s behalf. Putin demurred, but singled out the city as his electoral heartland, a kind of “real Russia” that lives simply, works with its hands, and reliably votes for Putin.

In the years since his election, he has lavished attention on the city of 350,000. A new mayor sent in from Moscow has built a fancy new esplanade and refurbished the city’s parks. The Kremlin has poured money into the two failing plants—thus they are idling instead of closing, and workers are furloughed rather than fired. An upscale hotel has gone up to host the conferences that everyone suddenly wants to put on in Putintown.

Life is still not great here, but it’s a loyal place and support for Putin is high. In large part, it is because people—especially older people like Kolsky—get their news from Kremlin-controlled TV. And Kremlin-controlled TV has been unequivocal about whom they want to win the U.S. presidential election: Donald Trump.

In its coverage of the American presidential race, Russian TV has been un-nuanced, to put it mildly. When the AP reported that Hillary Clinton had the required number of delegates to lock up the Democratic nomination, for instance, the evening newscast on the largest Russian national channel used the event as a peg to talk mostly about Roger Clinton’s umpteenth DUI. Usually, though, Kremlin TV’s Clinton coverage is about how she hates Russia and is a reckless warmonger. A particular obsession is Clinton’s joyous reaction to the news of Qaddafi’s death—“We came, we saw, he died”—probably because the manner of Qaddafi’s death is said to have deeply unnerved Putin, his old ally. Kremlin TV places the blame for what happened in Libya squarely and exclusively on Clinton’s shoulders and, as one news program put it, “The role of the Clinton family and of Hillary in particular in the American wars of the last couple decades is hard to overstate.”

Trump, on the other hand, is presented as a levelheaded pragmatist, a man who understands that America has overreached and that it needs to pull back. (Which, of course, is great for a Russia that has been on its own mission to overreach. Having America out of the way would make that far easier.) “Trump’s ideology is one of rejecting the destructive globalism of the last few years in favor of a healthy American isolationism,” one prominent pro-Kremlin commentator declared, adding that Trump’s saying that he will work with Putin infuriates American “globalists.”

My colleague Michael Crowley wrote about the Kremlin’s English-language channel RT pulling for Trump. But unlike RT, whose ratings are, shall we say, fudged, people actually watch regular Russian TV. Surveys show that 60 percent of Russians regularly watch Kremlin-controlled news shows to the exclusion of all other media, domestic or foreign. For 85 percent of Russians, television is the main source of news. A recent poll by the Kremlin-owned Interfax news agency found that Russians favor a President Trump to a President Clinton, three to one.

* * *

Since the winter of 2011, when, in the Kremlin’s view, then-Secretary of State Clinton dashed all hopes of a reset of Russian-American relations by declaring that year’s Russian parliamentary elections rigged, the television has been virulently anti-American. It is portrayed as Russia’s archenemy, constantly trying to bring Russia down and humiliate it, to check its ambitions abroad, and to dismember the resource-rich nation for its own personal gain. The resentment was always there since the collapse of the Soviet Union, lurking as perestroika hopes for a wealthy, democratic Russia quickly melted into a far more chaotic and disappointing reality. Like Trump, Putin has played this bitterness masterfully, spinning a tale of humiliated, diminished Russia returning to its old days of Soviet and Imperial glory. In the eyes of the overwhelming majority of his subjects, Putin has made Russia great again.

So it is no surprise that Felix Nikolaevich Kolsky, who regularly watches television—sometimes he has two sets going at the same time—has come away convinced of its main tenets: Putin is the only man for Russia (“You’d have to be an idiot to vote for anyone else!” he says), that Clinton is a belligerent who hates Russia, and that a President Trump would respect Russia and make peace with it. “She laughs when a person is killed, she is happy like a little kid,” Kolsky said of Clinton when we met in a café on the main square of Nizhny Tagil. “With that kind of personality, she would easily send America’s boys anywhere as cannon fodder!” As for Trump, he hopes he will pull America back off the world stage and stop going after Russia. “I have big hopes that, if he wins, the world will live peacefully for eight years,” he said. He likes Trump’s plan to cut NATO spending. “The Americans are dumping their budget into NATO and the Latvians”—fascists, the lot of them, according to Kolsky—“hide behind Uncle Sam. When Clinton becomes president, she’ll have NATO put weapons in the Baltics. In 1941, they kept saying Hitler won’t attack, Hitler won’t attack. But they had put so many weapons on our border, and of course they attacked!” (Kolsky also had harsh words for that other Russia hater, Condoleezza Rice. Or as he referred to her, “that mulatto woman.”)

He hopes his letter will give Trump a boost in the general election. “Maybe this letter be helpful, maybe he can publish fragments of it and maybe he’ll emphasize a friendship with Russia,” Kolsky said. The proposed donation, he hopes, will help, too. 100,000 rubles is just $1,500 these days, but it is four monthly salaries of the average resident of Nizhny Tagil and Kolsky’s granddaughter saves money on groceries by eating potatoes and cabbage from Kolsky’s garden. Kolsky, who plays the stock market in his retirement, doesn’t care, though. “I wish him victory in November,” he told me. “That’s the main idea.”

Read more: http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/06/donald-trump-russia-putin-213956#ixzz4BTvdPf5m

Follow us: @politico on Twitter | Politico on Facebook