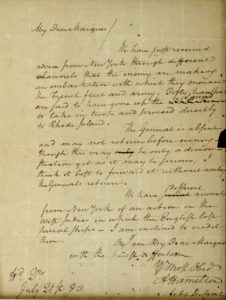

This image filed Wednesday, May 15, 2019, in federal court as part of a forfeiture complaint by the U.S. attorney’s office in Boston shows a 1780 letter from Alexander Hamilton to the Marquis de Lafayette, that was stolen from the Massachusetts Archives decades ago. The complaint asks a judge to order the letter returned to the state. It resurfaced in November 2018 when a Virginia auction house received it from a South Carolina family that wanted to sell it. The letter was part of a deceased relative’s estate. (U.S. Attorney’s Office via AP)

On July 21, 1780, Hamilton wrote a letter to Lafayette warning the British were moving against French forces in Rhode Island.

The letter ended up in the Massachusetts state archives, from where it was stolen by a “kleptomaniac cataloguer” sometime between 1938 and 1945, who apparently sold it into the rare books and autographs trade, from where it was purchased by one R. E. Crane, who (we’ll assume here) didn’t know it was stolen.

After Crane died, his grandson and heir, Stewart Crane, attempted to sell it. The auction house, suspicious of its provenance (i.e., chain of title), notified the FBI, which seized the letter. Crane sued to get it back, but the courts ordered it returned to the state archives. (Read story here, and the court’s decision here.)

In American law, stolen property continues to belong to its rightful owner, and subsequent purchasers (including innocent purchasers) can’t acquire legal title to it through possession. That principle is enshrined in our common law.

This case has a twist, though. State statutes, not common law, determined the outcome. And although a federal court decided the case, it based its decision on the state laws.

Those laws defined the letter as a “public record,” and required the state archives to keep and preserve it. In other words, it couldn’t legally be sold, given away, or abandoned. For this reason, only the state archives could own it, and no one else could acquire legal title to it.

In another interesting twist, the state sued the letter, not Stewart Crane. This was an “in rem” action, i.e. the lawsuit was brought against the property itself, and was a forfeiture action. Basically, that means the Crane family possessed the letter improperly, and not only aren’t entitled to keep it or sell it to someone else, but aren’t entitled to compensation for its confiscation.

Caveat emptor. Buyer beware. If it’s “hot,” it isn’t yours, and if you want your money back, you have to track down and sue whoever sold it to you, and he has to sue whoever sold it to him, etc. This is why, for example, hiring experts to trace provenance is so important when buying high-priced art to make sure the seller is able to convey good title (see, e.g., Nazi-looted artworks), although the legal technicalities are somewhat different in those cases.

Photo: An antiques dealer estimated this letter might sell for $35,000

The state may rue its action, as its ownership maybe somewhat spurious. Arguable the Federal government is the proper owner or even France as the letter was to Lafayette.

The state could end up discovering purchasing the item at auction or recompensing the Cranes might have been cheaper.

The letter has been public property since the founding of the Republic. Why do you think the state’s ownership is spurious? Neither the federal government nor France has put in any claim for it. How much would Mr. Crane have to spend on legal fees to keep fighting for an item he could maybe selling for $35,000? And as this decision was issued by a federal appeals court, the only possible remaining appeal is to the U.S. Supreme Court, and what are they chances they would take the case? Don’t they have more important things to do?