By Douglas W. House (condensed; read original here).

Traditional vaccines rely on a live-attenuated (weakened) virus [e.g., measles, mumps, rubella (MMR), rotavirus, smallpox, chickenpox, yellow fever] or whole-inactivated (killed) virus (e.g., hepatitis B, HPV, whooping cough, pneumonia, meningitis, shingles) to produce the desired immune response. The negatives include the potential to cause the disease it is designed to prevent (live-attenuated versions) and the need to deal with live virus in the development process.

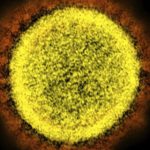

In COVID-19’s case, researchers did not need the live virus since Chinese scientists sequenced the genome of SARS-CoV-2 and published the results online in January. Based on previous research on cousins SARS-CoV-1 and MERS, investigators knew to focus their attention on the coronavirus’ spike protein that studs its surface and enables it to enter healthy human cells. Vaccines that expose the body to the spike protein alone, which is the antigen, should induce a protective immune response. This is the strategy behind most of the leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates. The good news is, this strategy means that many of the vaccines do not have to be kept at super-low temperatures during transport, so they’ll be easier to export to the countries that need them. However, some vaccines still need freezing temperatures to keep them effective, but luckily technology like these cryogenic labels makes exporting these sorts of vaccines a little easier.

Moderna’s mRNA-1273 and Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 are genetic vaccines that use messenger RNA (mRNA) to instruct the person’s cells to make the spike protein which, in turn, activates the immune response. Since mRNA is a fragile rapidly degraded molecule that does not easily pass through the cell membrane, both candidates use carrier molecules called lipid nanoparticles to transport it into the cytoplasm of the cell.

Other vaccines use a different (benign) virus, called a vector, to carry the spike protein coding sequence into cells. These are categorized as replication-defective (RD) or replication-competent (RC). The most popular RD choice for COVID-19 vaccines is adenoviruses, used in Johnson & Johnson’s Ad26.COV2.S, and AstraZeneca (AZD1222) and Oxford University’s ChAdOx1. The former uses human adenovirus 26 (Ad26) as the vector, while the latter uses a chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAd). In both vaccines, the adenovirus carries DNA coding for the spike protein into the nucleus of the host cell where its machinery produces the spike protein. Since the viral vector is replication-defective, no more viruses are produced after the first cell is infected.

Merck’s candidate V590 uses a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) vector while V591 uses the measles virus. Wild-type VSV is usually asymptomatic or causes mild flu-like illness in humans. Company scientists replaced part of its RNA sequence with RNA coding for the spike. Unlike adenoviruses, this rVSV vector displays the spike on its surface. Since it is replication-competent, it more closely resembles a real viral attack. This is the same platform the company uses in its Ebola vaccine, Ervebo, approved by the FDA in December 2019, the first and only viral vector vaccine to earn a U.S. nod to date.

Novavax’s NVX-CoV2373 is a stable prefusion protein based on its recombinant protein nanoparticle technology (uses a subunit of the spike protein) that includes its proprietary Matrix-M adjuvant. One of its advantages is that it is stable at cool temperatures (~36 – 46 degrees Fahrenheit) enabling distribution through standard vaccine channels.

The FDA has yet to approve any adenovirus vector vaccine or DNA or mRNA vaccine.