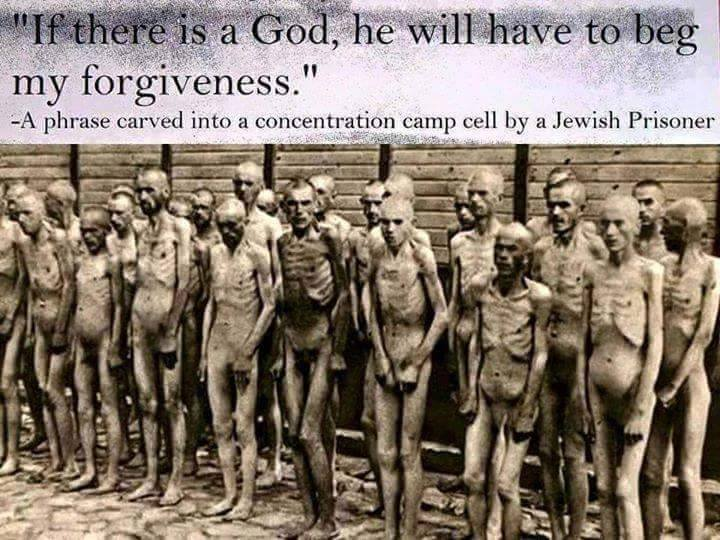

Imagine what this eve of Yom Kippur must have felt like in Buchenwald

The vow taken that night … whether sung in the original Aramaic or translated into any of the languages spoken in the camp … is called “Kol Nidre.” The vow, wherever recited, would have been the same:

All vows, obligations, oaths or anathemas, pledges of all names, which we have vowed, sworn, devoted, or bound ourselves to, from this day of atonement, until the next day of atonement (whose arrival we hope for in happiness) we repent, aforehand, of them all, they shall all be deemed absolved, forgiven, annulled, void and made of no effect; they shall not be binding, nor have any power; the vows shall not be reckoned as vows, the obligations shall not be obligatory, nor the oaths considered as oaths. (original text from aramaic)

As they recite Kol Nidre tonight, I hope my sibs understand that Kol Nidre is not a prayer, it is a vow.

The impact of this vow on Jewish law has special meaning for the legal fight over the photographs my father made as the first American physician to deliver healthcare to the inmates of Buchenwald.

I hope my sibs understand that Kol Nidre is a huge part of the identity we inherited from our parents … an identity forged in the very antsemitism that makes these pictures so important.

Antisemites have used the words of Kol Nidre as an argument that the word of a Jew can not be trusted.

Antisemites have used the words of Kol Nidre as an argument that the word of a Jew can not be trusted.

Even Jewish scholars have asked ask how, if every year Jews recites a prayer not for forgiveness by the Deity but for self absolution from oaths, how can anyone, Jew or goy, trust the word of a Jew?

The Czarist Russian government went so far as to decree that siddurim, Jewish prayer books, must include an explanation of the limited nature of the vows that could be released by this ceremony. Many rabbis have ordered Kol Nidre removed form the Yom Kippur siddur to avoid this slur on our ethics.

The modern rabbi’s answer to the charge is this: Kol Nidre is recited before many hours of Yom Kippur prayers urging Jews to seek resolve any wrongs we have done. That imperative, to fix any wrong you have done, intentionally or not, is called “Teshuvah” and is the message recited over and over again in the Yom Kippur service.

Again, Kol Nidre is not a prayer, it is a vow. Kol Nidre is recited before the prayers to recognize that teshuvah is impossible when the wrong is the result of failure to keep a vow that is coerced. Jews living in Europe, where our very identity was threatened by antisemitism, were forced to make vows we could not follow. The inmates in Buchenwald were forced to break Jewish laws, even deny their identity as Jews, in order simply to survive.

Kol Nidre recognizes that you can not atone for a commitment made under coercion.

I have three examples of the problem in my own behavior.

As an atheist I have a personal commitment not to pray in any way that would say to others, “I am also a believer.” I see such prayer a violation of the commandment not to take the name of the Deity in vain. As my Dad was dying, we sibs were gathered in a neighboring room. Despite my Dad’s devout atheism and knowing of my beliefs, my sister insisted that we three sibs recite a prayer together immediately after his death. I understood her need, but felt it was disrespectful to my father and asked to leave the room. She became angry so I stayed. I still feel the pain of that moment and the betrayal of my own and my father’s beliefs.

An even more enduring example came when it was time to place a tomb stone on my Dad’s grave. Dad had been married to his second wife, Betty, for over twenty years and loved her deeply. After his death, my brother and sister became involved in a legal fights over the provisions Dad had made for Betty. I stood up for my step mother and tried to argue for what I believe our father would have wanted. Their hatred for Betty and for her daughter Max, became the basis for my sibs hatred of me.

As an example, my brother and sister refused to include a mention of Betty on his tombstone. Intimidated by my brother, Betty agreed. I gave in too but have been upset that we, my sibs and I, permanently dishonored my Dad’s love for Betty. I will think of that tomorrow during Kol Nidre.

My third example came two years ago when the sibs met in a very angry confrontation over the terms of my father’s will. Many hurtful things were said. Still, we needed to resolve issues arising from my Dad’s will. Threats were made and there was much coercion. Moneys were transferred. Again I agreed to somethings I did not feel were correct. There was, however, a commitment by the sibs that the legacy of my father’s photographs from Buchenwald would be gifted to a proper institution where these very fragile pictures could be archivally processed, digitized and made available to the public.

Soon, “there may be no one left to tell their story.” … Irena Steinfeldt Antonin Kalina was one of the prisoner leaders of the revolt that liberated Buchenwald before the Americans arrived. As the Germans fled. Kalina, with other communist leaders, ran the day-to-day operations of Buchenwald on behalf of the Nazi SS. Thanks to Kalina’s efforts, when the Allies liberated Buchenwald, over 900 Jewish boys survived. When they were freed, the boys lifted up Antonin Kalina and carried him on their shoulders. After the war, Kalina returned to his home in Czechoslovakia and lived out the remainder of his life humbly in obscurity. The boys whom he saved didn’t talk about their experiences during the Holocaust .. a horror they wanted to be gone. However, about 15 years ago, some of the surviving boys, then around 80 years old, initiated a process to have Kalina recognized. A film was made “Kinderblock 66: Return to Buchenwald,” telling the story of four boys who went back for the 65th anniversary of their liberation from the camp. When the movie played to a full house at the Jerusalem Film Festival. , Irena Steinfeldt, a Director of Yad Vashem, announced that Yad Vashem was recognizing the humble man as among the Righteous Among the Nations along with many other heroic goyem.

That commitment has not been honored. I have tried to explain to my sibs that my goal is to publish my father’s pictures, pictures with his notes inscribed on the back, so the last survivors of the camps … including those who were then children … can see if they remember our father. I have told them I would like to publish the pictures with any comments I can get from the survivors so his grandchildren and now my granddaughter can learn from this remarkable story.

This may never be possible. I discovered the pictures five years ago. The survivors are dying off. The pictures are fading.

The potential for restoration of wrongs in my family may be seen in this interview with Antonin Kalina. Kalina was a prisoner in Buchenwald. when Robert Schwartz arrived. Kalina is now dead but his heritage shows a way we should be able to resolve our conflict.

Antonin Kalina was a Czech communist. In 1939, after the Nazis took over Czechoslovakia, Antonin Kalina,was imprisoned in Buchenwald.

In early 1945, as the allies advanced, the Nazis began liquidating their death camps. Jewish prisoners were put on brutal “death marches” toward Germany … some of the survivors ended up in Buchenwald.

Included among the Jews in Buchenwald were a large number of Jewish boys, then between the ages of 9 and 16.

Buchenwald was not liberated when Patton arrived, it was liberated by the prisoners as their Nazi keepers fled! It was the inmates fleeing through the forest of Buch that led our father and other GIs to discover the hidden camp.

Before the Nazis fled, they turned over much of the day-to-day operations of the camp to Kalina and his fellow communists. Kalina decided to place the youths in a filthy quarantine barrack. The SS was loathe to go into a place of such filth.

This kids’ barrack, number 66, became known as the “Kinderblock.” Antonin Kalina was in charge, of Kinderblock. Instead of assembling the boys twice a day with the other prisoners, he counted the boys inside the barracks. His boys did not go to work. They had access to blankets, and at times extra food rations. The block elders didn’t beat the boys, something almost unheard of within the Nazi camp system. The boys got to survive.

Finally, in early April 1945, the Nazis decided to eradicate Buchenwald’s remaining Jews. The SS commander ordered all

When the SS came around looking for Jews, Kalina told  them that block 66 had no more Jews. When Robert Schwartz arrived in the

them that block 66 had no more Jews. When Robert Schwartz arrived in the

camp, he must have found over 900 Jewish boys. I can only imagine the wonder these boys may have found when an American medic, our father, was a proud Jew, gave them health care.

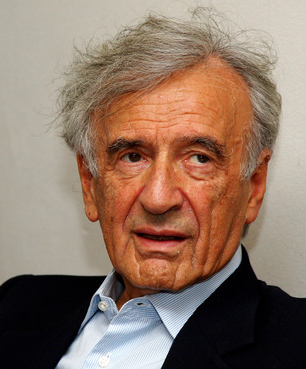

Amongst the boys who are still living today are the author Elie Wiesel and Yisrael Meir Lau,

formerly the chief rabbi of Israel.

So, isn’t the opportunity for Teshuvah clear? If these photographs are not preserved soon, the boys of Kinderblock will have died and the images will mostly have faded. I hope Hugh and Steph might instead join me in asking their rabbis and themselves about the unique Jewish concept of Teshuvah .. the resolution of errors.

Based in part on material that appeared in The Times of Israel.