As we approach Yom Kippur 5775 (2014 CE), today marks nearly the fiftieth essay in my Buchenwald series. This essay is posted during one of the ten days between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, days each Jew is supposed to spend thinking about how to be a better person …a process called “Teshuvah.”

As we approach Yom Kippur 5775 (2014 CE), today marks nearly the fiftieth essay in my Buchenwald series. This essay is posted during one of the ten days between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, days each Jew is supposed to spend thinking about how to be a better person …a process called “Teshuvah.”

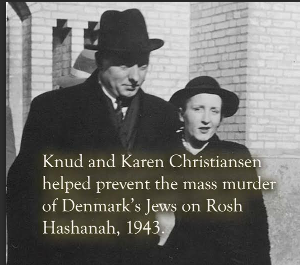

What better lesson than that of Knud Christiansen, a righteous non Jew? Mr. Christiansen was a world-class Olympic rower, a Danish hero in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. On this October 1, 2014 we are 61 years after Adolf Hitler ordered Danish Jews to be arrested and deported. Almost all of us survived and that is why Knud and Karen are living heroes. .

The young Knud Christiansen competed in the 1936 Berlin Olympics as a member of the Danish Rowing Team. Karen Rasmussen, later to be Knud’s wife, wrote letters home of the “terrible brutalization” of the Jews .. an impression reflected in her later experiences in Copenhagen as Mrs. Christiansen.

Though not about Buchenwald, today’s essay does reflect on the behavior of my brother and sister, Hugh Schwartz and Stephanie Quick, who driven by hatred of me, have dishonored my father’s role as a hero in the liberation of one of the camps . Denmark’s Jews would have ben sent to Buchenwald without the courage of Mr. Christiansen and other Danes. It is so sad that that, in their hatred for me, Hugh and Steph are trying to destroy my Dad’s writings and photography about Buchenwald. They badly need to leart about Teshuvah, Perhaps the story of a Danish couple .. a couple privileged by what the Nazis saw as an Aryan heritage … will soften their hearts

The Christiansen couple played a triple role in the Danish resistance. As Aryans and wealthy Danes, they belonged to the upper reaches of society. As patriots they worked in the resistance including acts of sabotage. They were also friends of the Jews.

The couple and their two children lived in a fashionable apartment in the Havnegadein neighborhood in Copenhagen. Of course the new elite, the Nazis, lived there as well. In occupied Denmark of 1943, Knud was successful in an industry mostly dominated by Jews, the manufacture of leather goods . When one family, the Phillipsons, were threatened with internment by the Nazis, Knud secured their release by promising to produce a propaganda film in which Germans were portrayed as friends of Denmark. The film was never produced.

The Christiansena were able to report on the comings-and-goings of the upper ranks of Nazis. Christiansen learned from his German neighbors of the SS plans to arrest all the Jews on Rosh Hashanah, at 10 p.m. on Oct. 1 in 1943. That knowledge led to the miraculous evacuation of the Danish Jews to neutral Sweden , saving almost all the Jews.

Knud Christiansens died recently in New York City. An email from his daughter Marianne describes this Christian in terms every Jew who observes Teshuvah should understand, ” During his 97 years in this world he took many opportunities to help those who came along in his path in small and sometimes big ways. He demonstrated in the way he lived how one can appreciate the smallest moments of human interaction and kindness. That when we engage fully with life the only thing of any importance is the love in our hearts.”

from The Jewish Post:

At first, Christiansen ushered large groups of Jews to farmhouses, churches and city apartments, using every available shelter to safeguard the Jews from immediate arrest. His youngest daughter, Jyttte, remembers her home was teeming over with guests in the living room, dining room and spare rooms in the back of the apartment, She was told to call the family’s guests “Uncle David, Aunt Sarah and Uncle Adam,” all of whom had decidedly Jewish names. One of the guests was the director of the Danish National Bank.

It isn’t without a sense of nostalgia that she recalls a young woman from Amaliegade, whose name has long been forgotten, but not the “delicious soup” she made for all the guests.

Mr. Christiansen’s own activities ranged from saving mostly “complete strangers” to rescuing close personal friends. One night in late September, Mr. Christiansen rushed to his weekly bridge game and urged two of his friends—Jewish brothers named Philipson—to immediately go into hiding. One of the brothers insisted on going home first, ignoring Christiansen’s offer to make arrangements for the brothers and their families. The next day Christiansen learned his friend had been arrested and placed in a detainment camp. He told the Danish Nazi that his friend was “only one-quarter Jewish,” hoping the perverse Aryan logic would convince the guard that his friend “really wasn’t Jewish.”

Mr. Christiansen’s own activities ranged from saving mostly “complete strangers” to rescuing close personal friends. One night in late September, Mr. Christiansen rushed to his weekly bridge game and urged two of his friends—Jewish brothers named Philipson—to immediately go into hiding. One of the brothers insisted on going home first, ignoring Christiansen’s offer to make arrangements for the brothers and their families. The next day Christiansen learned his friend had been arrested and placed in a detainment camp. He told the Danish Nazi that his friend was “only one-quarter Jewish,” hoping the perverse Aryan logic would convince the guard that his friend “really wasn’t Jewish.”

The commandant told Christiansen “too many Jews had slipped through the net,” all the while refusing to release the friend. Taking considerable risk to his own life, Mr. Christiansen carried his request to the highest-ranking Nazi in Denmark, General Werner Best, who was better known as the “Blood Hound of Paris” for ruthlessly deporting Jews in France to death camps.

Though the friend’s release was never fully explained, it appears that Mr. Christiansen’s status as a world-class Olympic athlete; and his father-in-law’s position as the private physician to the King of Denmark’s royal household may have factored into the turn of events. In addition General Best suggested to Mr. Christiansen, a handsome gentleman with Aryan features, that he “participate” in a Nazi propaganda film, “which would portray Germany as friends of Denmark,” Mr. Christiansen recalled. “The film was never made,” Mr. Christiansen added.

For the war’s duration, many Danes made up the network that helped Jews leave the country, but Mr. Christiansen and his family still stand out. His physician father-in-law opened his substantial size home on the shoreline to shelter large groups of escaping Jews; his mother, the owner of a famous chocolate shop in Copenhagen, allowed her business to serve as a meeting place for rescue workers; and his younger brother acted as a lookout on the beachfront for Jews being ferried across the channel from Denmark to Sweden.

His wife was in fact one of the most heroic members. For five years, Karen Christiansen, a highly educated woman, sustained the risk of publishing a newspaper called “Die Warheit” (The Truth), which translated BBC broadcasts from Dutch into German to inform Weirmacht soldiers of atrocities being committed by the Third Reich and the more realistic accounts of the Allied advances in the war. “My wife had a backbone made of steel,” says Christiansen, laughing. “She was tough and fearless.” Her acts of heroism extended to protecting resistance members and even caring for wounded allied soldiers as the war progressed.

As the Christiansens’ story has come forward, so have details suggesting that many Germans could be counted on to look the other way. “A lot of the German (soldiers) didn’t want anything to do with the war,” Mr. Christiansen says. “They were very young and wanted nothing to do with the killing of Jews.” Rescue workers and survivors have verified that boats were going back and forth under the eyes of the Germans, who did not attempt to block the operations. Still, the Gestapo made hundreds of arrests and Jews lived in dreaded fear of them.

After the war, Mr. Christiansen recalled that he could “not bear to look” at the white buses of emaciated Jews returning from Theresienstadt detainment camp (not a liquidation camp); the bittersweet feelings at the more fortunate parade of Jews returning from Sweden and dropping flowers of appreciation at his mother’s floral shop; and the scornful satisfaction of watching the Germans pack up and leaving Denmark on foot, after having confiscated all Danish vehicles for wartime use.