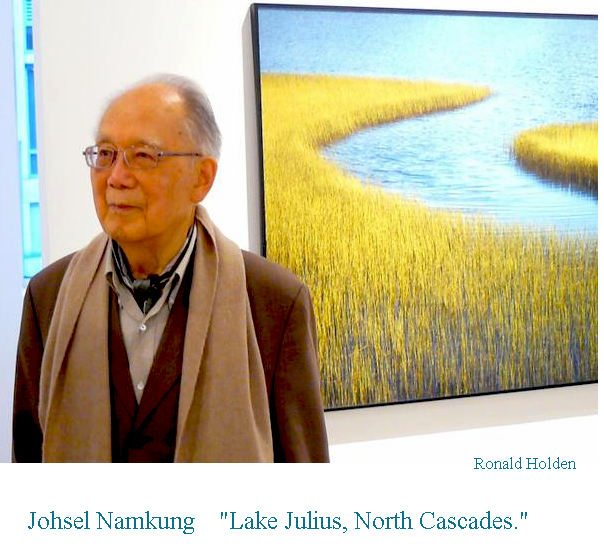

The Gordon Woodside / John Braseth Gallery in South Lake Union has works by Johsel Namkung. I highly recommend this show to anyone who loves the Northwest and the UW.

The Gordon Woodside / John Braseth Gallery in South Lake Union has works by Johsel Namkung. I highly recommend this show to anyone who loves the Northwest and the UW.

Johsel Namkung is a renaissance man. While never a member of our faculty, his amazing career is a tribute to the role the UW plays in Seattle’s remarkable mix of cultures.

Born in Korea before WWII, Johsel grew up in the hard times of the Japanese occupation. As the son of a prominent Christian family in Korea, Johsel studied classical western music in Japan and, in 1940, Johsel took first prize in the All-Japan Music Contest. as as an aspiring singer of German Lieder, During the war Johsel married Mineko, a Japanese woman, a printmaker and artist.

After the war, the Namkungs came here to Seattle where Johsel pursued a career as a singer of German Lieder. Mineko and Johsel opened a gallery devoted to Japanese prints, the Hanga Gallery.

About this same time Ansel Adams, a concert pianist, had formalized a tonal scale for photography, what Ansel called “The Zone System.” Like Ansel’s work, Johsel’s work, almost deceptively quiet, brought the vision of a singer of Lieder into photography. Johsel became a member of a community, now called the Northwest School. This great movement, inspired by Seattle’s mix of misty light and Asian influences in our culture , included Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves, William Cumming, Mark Tobey, George Tsutakawa, Paul Horiuchi, Tony Angell , and James Washington, Jr. The Northwest School was an aesthetic rather than only a graphic art form. Another member of the crew, the composer John Cage, painted with sound and used osound r tonality in his own paintings, much as Johsel still does in photography. Johsel’s love of Lieder never went away and I remember an amazing German tenor voice emerging from Johsel’s normally elegant use of English.

I got to know and love Johsel through a strange accident of my own. Johsel and Mineko became targets of the House Un American Committee, anticommunist mania of the US during the Korean war. The Namkungs were declared enemy aliens and slated for deportation. Because of the far right politics in South Korea of that era, deportation might well have meant death.

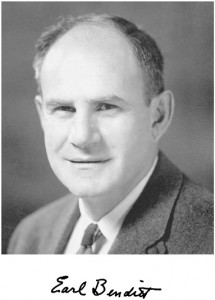

The Chairman of Pathology at that time, Earl Benditt, was a visionary. Though not an artist himself, Earl with his wife Marcella, was deeply involved in Seattle art. There home was remarkable for thec ollection of beautiful objects. Under Earl, the UW was a pioneer in use of the electron microscope, a tool that forced pathologists to think about disease at a cellular and a molecular level. Electron microscopy, however, was also an art form and Earl saw that a skilled photographer could be uniquely valuable translating the images made by these huge machines into images that biochemists could understand.

The Chairman of Pathology at that time, Earl Benditt, was a visionary. Though not an artist himself, Earl with his wife Marcella, was deeply involved in Seattle art. There home was remarkable for thec ollection of beautiful objects. Under Earl, the UW was a pioneer in use of the electron microscope, a tool that forced pathologists to think about disease at a cellular and a molecular level. Electron microscopy, however, was also an art form and Earl saw that a skilled photographer could be uniquely valuable translating the images made by these huge machines into images that biochemists could understand.

Earl hired an artist to make electron micrographs at the UW School of Medicine.

Others in the UW academic community worked with civil rights lawyers to defend Johsel and the musician stayed here, became a master, using musical tonality to create images of the submicroscopic world within cells.

While the rigor of the “zone system” made immediate sense to scientists. Not so incidentally, his new job gave Johsel access to great quality darkroon equipment . The line between making electron micrographs and printing his own work was never very obvious. A friend gave Johsel $500 to buy a Sinar 4 x 5-inch view camera and several lenses, which he used for his nature photography. I only wish we could have a show of Johsel’s amazing work with the lectron m icroscope to parallel hius unique vision as a nature photographer.

I came into this picture because of Viet Nam. I attended college during that war and was lucky enough to meet and work with the founder of electron microscopy, Keith Porter. Porter was one of the founders of “cell biology,” bringing together the abiity of the electron microscope to see structures within cells with biochemical knowledge of what cells do. In the early days of cell biology, traditional pathologists simply would not believe that these images were meaningful. As a student in Porter’s lab, I became one of the first generation of electron microscopists and, in some ways like Johsel, realized I needed to understand tonality to make believable images.

I went on to medical school during the Viet Nam war and was faced with the grim choice of being sent to Viet Nam as a general medical officer or fleeing to Canada. Dr. Porter told me about the Berry plan, a way to stay out of trouble by telling the draft that I was studying something useful. He tolsdme about the ‘s work in Seattle and urged me to contact Benditt. I did that and have been here ever since.

Working with Johsel was a challenge … sometimes the scientist and the photographer would fight over how to print an image. Oddly it was often I who pushed for richer use of tones while Johsel liked prints sharp to the level we might now call a “pixel.” This tension led me to become a fervent photographer and later to teach classes in fine print making and zone system at Orange Coast College, UCLA and here in Seattle. I became a founding member of a group of “art” photographers in the 70s here, largely centered around Infinity Gallery.

The Infintity crowd were all quite young, probably some of us were not very good, but we were all inspired by Johsel. He stimulated us all to develop high standards of print making. Even more importantly, his work, going back to the Northwest School , emphasized not just the process of photography but the discipline of taking the photographer knowing how you would use the medium to make that print. You can get some feel for how Johsel “sees” by going to his book, “Ode to the Earth” (published by Cosgrove Editions in 2006). Johsel Namkung describes “the loneliness and exultation” of reaching the top of the mountain and “standing all by yourself with your camera.”

At $5000 a print, Johsel’s work is a remarkable bargain. By comparison, the gallery is also showing works by Adams priced at $200,000. While I will not comment on art as investment, for me the quiet power of a Namkung print hanging on my wall is worth more than the drama of Ansels romantic images of nature.

Johsel’s books are available on Amazon.

The exhibit runs through October 15th; admission is free. Woodside/Braseth, 2101 9th Ave., 206-622-7243, www.woodsidebrasethgallery.com. Open 11 am-6 pm Tuesday-Saturday.