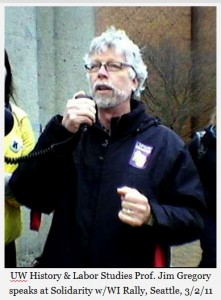

Ohio Senate Votes to Deny Collective-Bargaining Rights to Most Public-College Professors

Ohio Senate Votes to Deny Collective-Bargaining Rights to Most Public-College Professors

This time I may be siding with the enemy.

An article in the linked issue of the Chronicle reports that the Ohio State Senate is joining Wisconsin in ruling that faculty do not have collective bargaining rights.

While I believe every employee needs collective bargaining rights, it seems to me that faculty, especially at the UW, may be losing the wrong war.

American uni ons evolved around the needs of workers to protect themselves against predatory managers. If you are doing stoop labor, sewing skirts, or working on Henry Ford’s assembly line, your main concerns are working conditions, salary and benefits. As employees, we share those concerns, but, as faculty, we also have managerial responsibilities that may be even more threatened by the events in Ohio, Idaho and Wisconsin.

ons evolved around the needs of workers to protect themselves against predatory managers. If you are doing stoop labor, sewing skirts, or working on Henry Ford’s assembly line, your main concerns are working conditions, salary and benefits. As employees, we share those concerns, but, as faculty, we also have managerial responsibilities that may be even more threatened by the events in Ohio, Idaho and Wisconsin.

Our concerns center around the obligation of the faculty to set academic standards. Luddite politicians ought not to make decisions about whether we do or do not need to teach evolution. Liberal politicians may make be all to willing to dump excellence in the name of maximizing the number of Americans getting degrees. Administrators coming from outside of academics have no way of evaluating the value of a personal tutorial on Russian poetry versus an introductory English class. Regents coming from careers in real estate may not be well suited to decide if a branch campus is meeting the academic standards of a high level, research university.

In China, the Communist party bureaucracy determines what should be taught and how it will be taught. We may, unfortunately, be learning the wrong lessons from China.

When the administration at Oakland University (Michigan) made decisions about furloughs and class sizes, the Senate at that school refused to accept validity of these changes for the standards of that school’s mission. The courts upheld this decision by the faculty … faculty ARE management and DO have authority over what the school does.

The Washington State Supreme Court, in a case affecting another campus, ruled that the Code enacted by a Faculty Senate has the force of state law.

Why doesn’t the UW Senate act on this decision? The Aprikyan affair is a good example. The Senate Executive Committee has ruled that Professor Aprikyan was fired for scientific misconduct without due process. That decision by the Senate was a good thing, but where are the teeth in this biting decision? How does the Senate exercise the authority it, on paper ,has?

Coming back to Aprikyan, I attended a meeting yesterday where the assertion was made that responsibility for investigating charges of faculty misconduct lies with administrators, not even with the Chairs. Has this huge attack on faculty governance been enacted by the Faculty Senate?

As another example of the frailty of the UW Faculty Senate, look at the low profile they have played in the presidential search. Yes, there is token representation from the Senate on the Search Committee, but why has the Senate not debated the kind of president the faculty wants?

Senate not debated the kind of president the faculty wants?

At the risk of being seen as overly academic, I would like to quote from a primary source:

From the foreword to The Pogo Papers, Copyright 1952-53

“The publishers of this book, phrenologists of note, have laid hands upon the author’s head and report the following vibrations:

Herein can be found that rare native tree, the Presidential Timber, struck down in mid-sprout by the jawbone of a politician. Pogo returns to the swamp from a couple of political conventions to find his unfinished business being rapidly finished, once and for all, by rough and ready hands.

With that much information you are about as well equipped as anybody to plunge into the still waters of the Okefenokee Swamp, home of the Pogo people. The activities in this present book were spread shamelessly over the past drought-ridden year. Looking back across the fertilizer, small shafts of green can be seen here and there, while off in the distance wisps of smoke denote the harvesters at work.

Some nature lovers may inquire as to the identity of a few creatures here portrayed. On this point field workers are in some dispute.

Specializations and markings of individuals everywhere abound in such profusion that major idiosyncracies can be properly ascribed to the mass*. Traces of nobility, gentleness and courage persist in all people, do what we will to stamp out the trend. So, too, do those characteristics which are ugly. It is just unfortunate that in the clumsy hands of a cartoonist all traits become ridiculous, leading to a certain amount of self-conscious expostulation and the desire to join battle.

There is no need to sally forth, for it remains true that those things which make us human are, curiously enough, always close at hand. Resolve then, that on this very ground, with small flags waving and tinny blast on tiny trumpets, we shall meet the enemy, and not only may he be ours, he may be us.”

Article from the Chronicle follows below the fold.

By Peter Schmidt

A bill narrowly approved by the Ohio Senate on Wednesday contains even worse news for public colleges’ labor unions than they had feared: In addition to scaling back the collective-bargaining rights of all state employees, it would effectively prevent many faculty members from engaging in collective bargaining at all, by classifying them as managers, exempt from union representation, if they engage in any of several activities traditionally associated with their jobs.

The language dealing with how faculty members are classified was inserted into the bill Wednesday, just hours before the full Senate vote, as part of a 99-page omnibus amendment introduced Tuesday by the bill’s sponsor, Shannon Jones, a Republican.

“We were completely blindsided by it,” said Cary Nelson, president of the American Association of University Professors, which has local chapters on eight Ohio public university campuses that represent faculty members in collective bargaining. “We have just started to fight,” he said. “We are not going to settle for this.”

The classification provision defines as “management-level employees” those faculty members who, individually or through faculty senates or similar organizations, engage in any of a long list of activities generally thought of as simply part of the jobs of tenured and tenure-track professors. Those activities include participating in institutional governance or personnel decisions, selecting or reviewing administrators, preparing budgets, determining how physical resources are used, and setting educational policies “related to admissions, curriculum, subject matter, and methods of instruction and research.”

The Senate passed the measure containing such language—a bill overhauling the state’s collective-bargaining laws—on Wednesday by a vote of 17 to 16, with six Republicans joining all of the Senate’s Democrats in opposing it. The bill is expected to have an easier time getting through the Ohio House of Representatives, where Republicans hold a 59-to-40 majority, and to be signed by Gov. John R. Kasich, a Republican, who on Wednesday issued a written statement applauding its passage by the Senate.

“This is a major step forward in correcting the imbalance between taxpayers and the government unions that work for them,” the governor’s statement said. “Our state, counties, cities, and school districts need the flexibility to reduce their costs and better manage their work forces, and taxpayers deserve to be treated with more fairness.”

More Limiting Than ‘Yeshiva’ Decision?

Mike Maurer, director of the AAUP’s department in charge of union organizing, on Wednesday called the reclassification provision in the measure “virtually unprecedented.”

At private colleges, many faculty members are already legally classified as managers, and are thus precluded from collective bargaining, as a result of a 1980 U.S. Supreme Court decision requiring the decertification of a faculty union at Yeshiva University. But that ruling did not cover public college faculties, and no states have legislated such a change, Mr. Maurer said.

In an interview, Mr. Maurer said the Ohio measure would actually have a more drastic impact on faculty members at public colleges than the Supreme Court’s decision 31 years ago, in National Labor Relations Board v. Yeshiva University, had on faculty members at private institutions. The Yeshiva decision applied only to full-time faculty members who are determined to have significant control over managerial functions such as hiring, designing curriculum, and awarding tenure, and leaves such faculty members free to organize and operate collective-bargaining units if the college where they work does not petition the National Labor Relations Board to decertify their union. The Ohio measure, by contrast, appears to automatically preclude from collective bargaining those faculty members who engage in any management activities at all, Mr. Maurer and others said.

“It is trying, in essence, to put every faculty member in the managerial level,” said Jack Fatica, a professor of accounting at Terra Community College, in Fremont, Ohio, and the president of the Terra Faculty Association, an affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers that represents faculty members on that campus.

“It is going to basically take the union away from people,” Mr. Fatica said. If presented a choice between belonging to a union or having a say over aspects of their job such as curricular decisions, most faculty members will give up their union membership, he predicted.

Mr. Nelson of the AAUP quipped that about the only faculty members who would qualify for union membership under the Ohio measure are a few “on life-support machines in hospitals.”

No-Strike Rule

Although the bill no longer contains a flat-out prohibition against collective bargaining by public employees, as it did originally, it nonetheless contains a long list of other provisions that the employees’ unions oppose. For example, it prohibits public employees from striking, providing fines and jail time for those who do so. While allowing unions to negotiate their wages, hours, and terms of employment, it does not let them negotiate in many other areas, such as the setting of health-care and pension benefits.

The bill contains what appears, on the surface, to be a victory for public colleges’ part-time faculty members and graduate-student employees: a provision that for the first time includes them in the state’s collective-bargaining law and therefore allows them to form bargaining units. But Matthew A. Williams, vice president of the New Faculty Majority, an Akron-based national advocacy group for adjunct faculty members, said he suspects the provision was inserted in the bill because otherwise part-time faculty members and graduate students who work for colleges would have retained the legal right to stage strikes.

“We have been fighting for parity, but we never thought it would come in this form,” Mr. Williams said. “If you don’t have the ability to strike, where is the negotiating leverage?”

Where faculty members are precluded from collective bargaining because of their involvement in management activities, they might end up having less say over management than they did before. That is because the union contracts at many Ohio public colleges cover a long list of management-related issues, such as the rules governing faculty searches, the mechanisms for ensuring due process for faculty members who face discipline, and the criteria for awards of merit pay.

“You bargain, to some extent, over how much you are going to be paid. But just as big a deal as that is how it is distributed and whether it is going to be distributed in a fair way,” said Rudy H. Fichtenbaum, a professor of economics at Wright State University and a member of the board of the Ohio state conference of the AAUP.

I worry that the fight between unions and Tea Party Republicans may be lost twice …

First in the battle for the rights of faculty as employees .. human rights ALL working Americans should share.

Second, on campus itself. What happens, if university faculty end up as peripherated as public school teachers are from governance, even with a union to represent our rights as “workers?”

Is there a way of combining both aspects of the effort? How are faculty at Evergreen, ma very high quality unionized public college dealing with this crisis?

Thanks for this. While I see what you’re saying, I think you provide the response to your argument with the examples you give about the faculty senate at UW. As the UW administration has proven again and again, it’s pretty easy to ignore a senate. There are all of your examples and also what Emmert did to your salary policy on his way out of town. It’s also important to note that senates exist at the pleasure of the board of regents. They could unilaterally abolish the senate tomorrow. And while, the senate theoretically controls the curriculum, I would be willing to bet that there are all kinds of places at UW (especially in extended ed) where curricular decisions are being made without consulting the faculty.

The Ohio vote is a loss on both of the fronts you describe. We emphatically are not managers. We are labor who, in academic traditions, control how some of our labor is deployed (i.e. in curriculum). Doing away with collective bargaining weakens that. In our contract, the faculty senate, and to some extent their right to control curriculum, is protected. Our board cannot simply get rid of that with a stroke of the pen, the way they can at non-unionized campuses.

Best,

Bill

Thanks for sharing your post, which I had actually read a bit earlier in the day.

I think you have a point– namely that faculty can embrace their role as managers via the Faculty Senate.

We had this debate on WWU’s campus when we chose to unionize. Some very thoughtful people said that a union would undermine the collaborative governance model. I was torn, but ended up going with the union because I was convinced by the union’s spokespeople that one of the union’s goals was to strengthen the Faculty Senate.

And in fact that is what has happened. The union contract mandates the administration to grant the WWU Faculty Senate its role in curriculum. This guarantee was sought in part because the Senate’s role was being threatened by the previous administration, and faculty wanted to be able to reassert their control.

In Idaho, the Board of Directors of the University of Idaho just abolished the Faculty Senate by fiat, which I believe also happened at RIT (??), suggesting that Faculty Senates are threatened overall.

The current WWU administration is not challenging the Senate, but at the same time there are some important issues (like extended education for revenue purposes) where the union contract obliges the university to take the Senate seriously. Otherwise, the faculty might not have been able to get as involved.

Simply put: a good union contract reinforces rather than undermines faculty control over the curriculum, and takes away the Board of Directors’ right to abolish the Faculty Senate at will.

Finally, I would add that it is an oddity of American law to make such a distinction between managers and workers, and one that probably is meaningless in many ways (but real in American law).

The larger issue is one of democratic control. Because unions engage in collective bargaining over wages and benefits, they can protect public workers– including faculty– from the tyranny of the majority. Right now, for example, our contract insulates us from some pressures, and allows us to work with the administration to address WWU’s financial crisis. Otherwise we would be subject to their decisions on matters outside the curriculum.

The reality is this: when the threat to public sector unions reaches Washington, faculty are going to have to join with other unions to defend democracy in the workplace. Our entire political system is premised on checks and balances to protect citizens from arbitrary power– including the separation of powers; federalism; local authority; and bills of rights. If states are capable of violating rights, this makes unions vital to the public sector. They are part of the system of checks and balances.

This is probably more than you wanted, and more rambling than it ought to be.

Sincerely, Johann

——————————-

Johann N. Neem

Department of History

Western Washington University