When a Republican president replaces a Democratic president, you expect a drastic shift in how America’s antitrust laws are enforced. Specifically, you expect Republicans to be more lax about enforcing them.

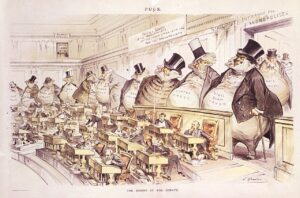

America’s stable of antitrust laws sprang from the monopolistic abuses of the late 19th century during the Progressive Era of the early 20th century (picture below; read brief history here). The popular conception is these laws broke up octopus-like monopolies (e.g., Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust detailed here), and today are used to block mergers deemed anti-competitive. (An example is government opposition to a proposed merger of the Kroger and Albertsons grocery chains).

Republicans, Trump included, are pro-business and anti-regulation. So expect less antitrust enforcement and more corporate mergers. But change will go even deeper, potentially all the way to a shift in guiding principles.

On that subject, there are two conflicting schools of thought: The “customer welfare standard” favored by conservative adherents of the Chicago School of economics (described here; think of Milton Friedman and George Stiglitz), and the New Brandeis Movement (described here) preferred by today’s progressives.

Beginning in the 1970s, and for decades after, there was a consensus that “the goal of antitrust is to prevent harm to competition,” and “firms shouldn’t engage in conduct or mergers to enhance market power unless that market power comes from innovation, investment, competence, or efficiency.”

“There was also a consensus that antitrust [practices] should protect competition rather than competitors,” and a “broad recognition that the consumer welfare standard should be the guiding principle” with the goal of “maximizing the wealth of U.S. consumers.”

I’m quoting from an article by Jay Ezrielev (profile here) in Barrons, a weekly investing magazine, at page 54 of their November 18, 2024, print edition. The entire piece is here, but I’m not sure you’ll be able to access it without a subscription.

When Biden took office, he broke with the consensus and embraced the “New Brandeis School” approach, led by his Federal Trade Commission appointee Lina Khan. That approach, which she adopted, steers antitrust enforcement to broader policy goals like addressing wealth inequality and protecting workers from unfair treatment. Conservatives complained it “weaponized” enforcement to pursue political causes.

Soon there’ll be a new sheriff in town. But despite the Republican pro-business bias, and conservative affection for the customer welfare standard, Trump might not reinstate the old consensus. He likes weaponizing government too much. His vice president to be, J. D. Vance, even likes Lina Kahn to some extent, although it’s unlikely Trump will keep her on at the FTC.

But if Trump continue her approach, you can pretty much count on him to twist it beyond recognition in service of his goals. He, too, may use FTC enforcement authority to pursue political goals but they’ll be different ones, and the targets of enforcement actions will be different, too.

He’ll likely go after companies that send jobs overseas, use foreign suppliers, and hire illegals. But if he does, courts may put the brakes on it, as they did on some of Kahn’s initiatives. One thing you can almost certainly count on is the lawyers will be kept busy.