A river runs through a controversy that has brewed for 20 years, but is now coming to closure.

A river runs through a controversy that has brewed for 20 years, but is now coming to closure.

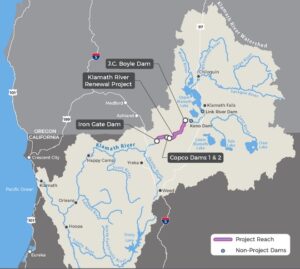

Historically, the Klamath River (map, left) was the third most productive salmon river in the lower 48 states, behind the Columbia and Sacramento rivers, Wikipedia says (here).

During the 1850s, gold seekers decimated the tribes whose ancestors fished the river for 7,000 years; then dams built between the 1910s and 1960s decimated the fish population (read brief history here).

In 2002, a major fish kill (of the fish that were left) sparked to a movement to remove the dams. A major opponent was Warren Buffett, owner of PacificCorp, who isn’t the warm and fuzzy capitalist everybody thinks he is (see details here and here).

But opponents wouldn’t prevail in the end; on Thursday, November 17, 2022, the Federal Energy Regulation Commission (FERC) unanimously voted in favor of removing the four lower dams on the Klamath (see story here). The leader of the Yurok tribe said, “The salmon are coming home.”

PacificCorp now has to surrender its dam license. The physical process of dam removal involves building roads for heavy equipment, drawing down the reservoirs, then proceeding with demolition, with the first dam to be breached by October 2024. When completed, the Klamath River dam removal project will be the largest in world history (see story here) — for now.

There’s little doubt the salmon will return. In his 2004 book, “King of Fish,” geologist David Montgomery described salmon as terrific colonizers. To breed in Pacific coastal rivers, they had to be; the Pacific salmon species and their ancestors have endured volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and changing landscapes for millions of years. (Get the book here.)

Montgomery, it should be noted, didn’t consider dams the biggest culprit in the salmon’s decline. As he pointed out, the Columbia River runs were already crippled by overfishing before the first dams were built. And, contrary to popular belief, the rivers were not the salmon’s main breeding grounds; low-lying lands, drained for farming, were; and even today a few salmon can be seen swimming across flooded roads in springtime in those areas (video below).

Anyone living out west knows (or should) that Native American culture and subsistence were tightly bound to the salmon runs for thousands of years until white settlement, farming, commercial fishing, industrialization, and dam building reduced the great salmon runs numbering in hundreds of millions of fish to a trickle. Today the salmon runs are about 1% to 2% of what they used to be.

Anyone living out west knows (or should) that Native American culture and subsistence were tightly bound to the salmon runs for thousands of years until white settlement, farming, commercial fishing, industrialization, and dam building reduced the great salmon runs numbering in hundreds of millions of fish to a trickle. Today the salmon runs are about 1% to 2% of what they used to be.

In recent years, politics and public sentiment have shifted, and the federal government is now making major investments in salmon recovery, with states and tribes as partners. And although dam removal has been slow to get off the ground, with initial focus on obsolete dams, it has begun.

The White Salmon River (a Columbia River tributary in Washington) became free-flowing in 2011 (details here), and the Olympic Peninsula’s Elwha River became free-flowing in 2012 (details here). With the Klamath River victory, the next fight will be over Snake River dam removal (see article here).

Dams, once considered synonymous with progress, come with environmental costs; they disrupt river ecosystems, and trap silt and pollutants. In 1954 a midwest newspaperman named Elmer Theodore Peterson (bio here) published a book called “Big Dam Foolishness: The problem of modern flood control and water storage,” which I read as a teenager.

Although his book had limited influence, the dam building era was coming to an end in the U.S. around that time (although it’s alive and well in Central America, see article here), and removal of smaller dams was already well underway (see article here).

We live in a world where wild rivers have to compete with the demands of a still-growing human population and until recently ignorant and uncaring attitudes toward the environment and wild places (views still held by the political right in the U.S. and elsewhere). People are slowly learning there are other ways to get electricity, and dams can’t create more water where there isn’t enough for human needs.

We live in a world where wild rivers have to compete with the demands of a still-growing human population and until recently ignorant and uncaring attitudes toward the environment and wild places (views still held by the political right in the U.S. and elsewhere). People are slowly learning there are other ways to get electricity, and dams can’t create more water where there isn’t enough for human needs.

Someday soon, the Colorado River dams may be useless artifacts (see article here and photo at left). For some rivers farther north, leaping salmon may be seen again.

But not in the vast numbers that Native Americans and early settlers took for granted; in the 19th century, there were so many they were used as farm fertilizer in Oregon.