It happens every time.

Gas prices are cyclical; they go up, come down. Nobody complains about cheap gas; but every time it goes up, Democrats want to slap “excess profit” taxes on oil companies. They talked about this in the 1970s, and now they’re talking about it again (see story here).

To which I respond, what excess profits?

James Carville, who was Clinton’s campaign manager, says “the system is being gamed,” but doesn’t explain how.

It was, beginning in 2014, but not by the oil companies and certainly not by your local gas station. Gasoline is a competitive market with many players. Some are governments. Only one government is in a position to “game” the global oil market, and that’s Saudi Arabia. And it does. Russia, too, is one of the world’s biggest oil producers and exporters, but they didn’t ask to be sanctioned.

In 2014 the Saudis flooded the market to drive down prices. Their goal was to bankrupt a new competitor, the U.S. shale industry. They intended to drive oil prices below shale producers’ breakeven costs, but the scheme failed because America’s shale operators figured out efficiencies that lowered their costs. But for several years the low oil prices engineered by the Saudis starved the oil industry of funds to invest in exploration and production.

Those chickens are now coming home to roost in the form of diminished supply. The pandemic crushed demand for a couple years, which postponed the reckoning, but now people are driving and flying again, and the supply isn’t there to meet spiking demand.

In Economics 101 you learn that in free markets prices are set by supply and demand, and pricing is a correcting mechanism for imbalances. E.g., when demand exceeds supply prices go up, reducing demand and incentivizing producers to increase supply, until the market is balanced again. Conversely, when supply exceeds demand, prices fall until the market rebalances by increasing demand and reducing supply.

If you tinker with that by imposing price controls, you get shortages (e.g., the Great Toilet Paper Shortage under Nixon’s price controls). So, tinker at your peril.

While you were enjoying cheap gas in 2020, oil companies were losing money. Now, they’re making up for those losses. Tinker with that, and you’ll be setting up the next shortage.

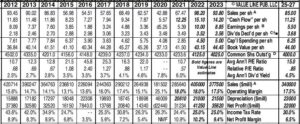

Below is an extract from the May 27, 2022, Value Line Investment Survey report on Exxon. I picked Exxon because it’s the largest and best known oil company, and is representative of the industry as a whole. This report shows Exxon’s profits were halved in 2015, halved again in 2016, and the company lost over $22 billion in 2020. It also shows a large drop in capital spending after 2015, which is your future supply. It costs money to get oil; if you choke off that money, there’ll be less oil.

As I said, gas prices are cyclical, and result from either too much (2020) or too little (2022) supply relative to demand. To lose money in some years, oil companies have to make more money in other years. Would you rather have $5 gas, or no gas? It averages out over time (probably somewhere around $3 a gallon).

As I said, gas prices are cyclical, and result from either too much (2020) or too little (2022) supply relative to demand. To lose money in some years, oil companies have to make more money in other years. Would you rather have $5 gas, or no gas? It averages out over time (probably somewhere around $3 a gallon).

Democrats are demagoguing this hot-button issue in what’s shaping up as a tough election year because they’re on the defensive. Even though they didn’t cause these high gas prices, they’re getting blamed for them.

You can’t get something for nothing. A couple years ago, oil companies were subsidizing your cheap gas. At some point they have to make good those losses. These profits are temporary. So are these gas prices.

Leave well enough alone. The market is self-correcting. This ship will right itself if politicians don’t screw around and unbalance it again. Meanwhile, as the Value Line data show (click on image below to enlarge), oil company profits aren’t excessive. In good years, they’re in line with what other industrial companies make for their shareholders.