South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem (photo below), a Republican, is pushing a bill that “would require public school districts to provide a daily moment of silence for ‘voluntary prayer, reflection, meditation, or other quiet, respectful activity,'” the tabloid Daily Mail reported on Monday, December 13, 2021 (read story here).

For reasons explained below, I don’t have a problem with it.

School prayer is a contentious issue in American politics (for history and legal rulings, go here). The First Amendment, often thought of as the free speech amendment, also includes the following,

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; …”

Known as the “establishment” and “free exercise” clauses, and also referred to as “separation of church and state,” this language prohibits government from establishing a state religion, favoring one religion over others, or interfering with religious practices. (The latter prohibition isn’t absolute; for example, states can prohibit polygamy even as a religious practice.)

For centuries, Europe was wracked by religious wars. Many of America’s early immigrants came here fleeing from religious persecution. So keeping government’s beak out of religion was, from the beginning, a cornerstone of this country’s freedoms. There was genuine fear that allowing government involvement with religion would bring those conflicts here.

Some religious observance is more intrusive than others, however, and drawing the line can be tricky. For example, “In God We Trust” is the official motto of the United States, and on our money; and the phrase “under God” is in the Pledge of Allegiance. These are not innocent insertions; in their modern iterations, they represent efforts by religionists to chip away at prohibitions they consider anti-religion.

However, because they refer to a generic “God,” and don’t prefer one religion over others (although they do prefer religion over agnosticism and atheism), such observances can be rationalized as not violating the spirit of the establishment and free exercise clauses. They also fall under the rubric of “civic religion,” a construct that purportedly embodies the “implicit religious values of a nation” (read more here). More importantly, they’re popular. Nobody objected.

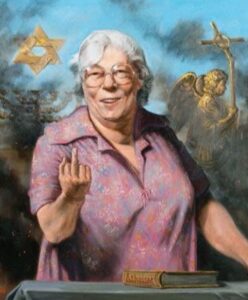

Until Madeleine Murray O’Hara (bio here), an atheist, came along and upset the apple cart by waging a legal war against public school prayer. She won court rulings that struck down widespread practices. (She ended up in a barrel, chopped up and burned, but not because of that. Her kidnapping and murder were committed by a felon stealing from her organization.)

Until Madeleine Murray O’Hara (bio here), an atheist, came along and upset the apple cart by waging a legal war against public school prayer. She won court rulings that struck down widespread practices. (She ended up in a barrel, chopped up and burned, but not because of that. Her kidnapping and murder were committed by a felon stealing from her organization.)

Drawing First Amendment lines on government “accommodation” of religion, a legal device (some might say subterfuge) used by courts to allow some government involvement with religion not rising to interference (see more here), is difficult because people don’t agree where the line should be drawn. For example, there have been fights over Christmas displays at public buildings.

(Some people don’t think there should be any line at all, and argue America is a “Christian nation” which should be governed by “Christian values” — which, for some, includes discriminating against gay people. However, it’s hard to see how this could possibly be reconciled with the First Amendment; and it’s usually promoted by people who show little respect for other people’s constitutional rights.)

The First Amendment’s religion clause is widely misunderstood. Some people think it prohibits prayer in schools, especially in the wake of the courts’ school prayer rulings. It doesn’t. The clause only applies to the government, never private individuals. Teachers and school administrators act as, and with the authority of, government agents, so any prayer organized, led, conducted, or encouraged by them probably violates the religion clause. (This doesn’t apply in parochial or private schools.)

But students aren’t government agents, they’re private individuals. They can pray in classrooms, as long as it isn’t disruptive. And there always has been, and still is, plenty of prayer in schools; it’s just not apparent because most of it is silent prayer. Students can, and do, pray all they want to. (As in, “Please, God, help me pass this test.”) It’s been my experience there’s a lot of praying during final exams. I did some of it myself.

Gov. Noem’s bill doesn’t appear to authorize teachers to conduct or organize prayers; it only provides for a “silent minute” that students can do with as they please. Not all will be praying (use your imagination here). On the surface, therefore, it doesn’t appear to run afoul of the First Amendment religion clauses. However, it could if there’s an expectation that it will be used for prayer. And Noem being who she is, and Republicans being prone to chip away (or carve away, if they can) at other people’s constitutional rights, no one will believe that isn’t her intent; and the ACLU probably will sue.

In any case, I don’t get to decide these matters; I’m only expressing my view of it. If the legislature passes her bill, and it probably will, the courts will have final say about whether it violates the First Amendment or not.

Photos: Above, Madeleine Murray O’Hare, grandma in a barrel; below, Gov. Kristi Noem bloviating at a rightwing confab