Natives of the region never gave it a name, because it isn’t visible from any inhabited place, so they didn’t know it was there. Its existence remained unknown to the world until 1856, when it was spotted by a British surveyor, who designated it “K2” on his maps — the only name that stuck, and is still used today.

To see the great pyramid-shaped mountain, which towers 2,000 feet above its giant neighbors, you have to make a long arduous trek (description and photographs here) through gorges and up glaciers until you come to a place called “Concordia” where two large glaciers meet, which lies in the heart of the Karakorum range in Pakistani Kashmir. (Photo right: view of K2, many miles away, from Concordia base camp.)

To see the great pyramid-shaped mountain, which towers 2,000 feet above its giant neighbors, you have to make a long arduous trek (description and photographs here) through gorges and up glaciers until you come to a place called “Concordia” where two large glaciers meet, which lies in the heart of the Karakorum range in Pakistani Kashmir. (Photo right: view of K2, many miles away, from Concordia base camp.)

The first westerners ventured up the Baltoro glacier in the 1890s, and the first attempt to climb K2, which didn’t get very far up the mountain, was in 1902. A serious expedition led by an Italian duke in 1909 camped at a spot used by every subsequent expedition as a base camp, got above 20,000 feet on what would become the standard route (i.e., easiest and most often used), and brought back world-famous photographs of a mountain that looks somewhat like the Matterhorn but is twice as high. But at that point, most of the route lay above the duke’s high point and was still unknown, he deemed it unclimbable, and didn’t return for another attempt.

The next attempt was a 1938 American expedition (details here) that reached 26,000 feet using the route discovered by the duke, which threads its way through House’s Chimney (photo, left), a 100-foot-high vertical crack now festooned with weathered ropes that might break under your weight.

The next attempt was a 1938 American expedition (details here) that reached 26,000 feet using the route discovered by the duke, which threads its way through House’s Chimney (photo, left), a 100-foot-high vertical crack now festooned with weathered ropes that might break under your weight.

In 1939, another American expedition (details here) came within 800 feet of the summit in good weather, but was turned back by slow progress and lack of time, and then lost of four of its climbers.

After World War 2, Dr. Houston returned in 1953 with another American expedition (details here), which encountered storms and fell well short of the 1939 mark, losing one of its members (and nearly the entire team). The Italians reached the top the following year (details here). Since then, nine other routes to the summit have been established, all of them more difficult.

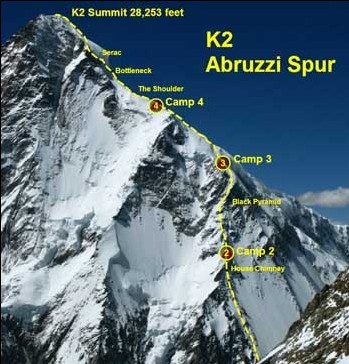

The standard route (description here, diagram below) “follows an alternating series of rock ribs, snow/ice fields, and some technical rock climbing on two famous features, ‘House’s Chimney’ and the ‘Black Pyramid.’ Above the Black Pyramid, dangerously exposed and difficult to navigate slopes lead to the easily visible ‘Shoulder’, and thence to the summit. The last major obstacle is a narrow couloir known as the ‘Bottleneck’, which places climbers dangerously close to a wall of seracs that form an ice cliff to the east of the summit.”

The standard route (description here, diagram below) “follows an alternating series of rock ribs, snow/ice fields, and some technical rock climbing on two famous features, ‘House’s Chimney’ and the ‘Black Pyramid.’ Above the Black Pyramid, dangerously exposed and difficult to navigate slopes lead to the easily visible ‘Shoulder’, and thence to the summit. The last major obstacle is a narrow couloir known as the ‘Bottleneck’, which places climbers dangerously close to a wall of seracs that form an ice cliff to the east of the summit.”

That route also requires ferrying supplies across a very steep traverse between camps 2 and 3 with a large drop below (photo, right). All of these obstacles lie at high altitude, which increases the climbing difficulties. But while not exactly a tourist hike, a known route and vastly improved equipment have made it easier, and commercially-guided parties now make the climb.

The irony of K2 is that a mountain so big could remain hidden for so long. People didn’t know it existed until the mid-19th century. Although about 750 feet lower than Everest, it’s a more difficult mountain to climb because of its steepness, and is climbed much less frequently because of its remoteness — and the fact it requires more climbing skill and is more dangerous.

There’s something about hills that makes people want to climb them. Something in human psychology has always drawn people to yearn for the view from the top, no matter how great the difficulty and danger. One suspects people were scrambling up the Great Pyramids of Egypt as soon as they were built. Then, the soaring peaks of the Himalaya, including the Great Pyramid of Baltoro, were unknown to the civilized world. And not until the modern era did methods and gear exist to make them accessible to the most intrepid of climbers, and there was considerable loss of life along the way. Still, the climbers kept coming, and still do.