With an evenly divided Senate, the Democrats need every Democratic and independent senator’s vote to pass legislation opposed by Republicans, which is most of Biden’s and his party’s agenda.

With an evenly divided Senate, the Democrats need every Democratic and independent senator’s vote to pass legislation opposed by Republicans, which is most of Biden’s and his party’s agenda.

Topping the list is protecting Americans’ right to vote from Republican state-level vote-suppression efforts, which has no hope of Senate passage without bypassing that chamber’s filibuster rule.

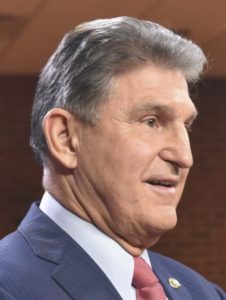

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-VA) has emerged as a pivotal figure in legislative battles requiring the Democratic-independent faction to stick together.

On the Covid-19 relief bill, he held out for a compromise with Republicans that reduced unemployment benefits, but didn’t yield to the GOP on state and local government aid, and ultimately voted for the bill. (Not one Republican did, and it passed 50-49.)

Manchin also publicly opposes eliminating the filibuster. The relief bill could pass despite the filibuster because it was a budget bill that’s exempt from being filibustered. But the voting rights bill — already passed by the House — and isn’t, and it and most of Biden’s agenda will go down in flames if 60 Senate votes are needed to pass it.

So why is Manchin catering to obstructionist Republicans? The short answer is he isn’t, but he does feel strongly about “minority rights,” involving the opposing party in the legislative process, and giving them a chance to contribute to writing legislation. He calls that “governing from the middle.”

Manchin’s appearance on Sunday talk shows on February 7, 2021, shed led on his thinking.

In a Fox interview, reported by CNN here, Manchin said the filibuster “defines who we are as a Senate,” but also said he’d make it “more painful” to use it. And in an NBC interview, reported by Huffington Post here, he reiterated his opposition to eliminating the filibuster “because he believes doing so would suppress the minority party’s input” but believes “invoking the procedure should be more painful.” Elaborating, he said, “Together, we’ve gotta make this place work,”

It boils down to Manchin’s concept of the Senate as an institution, and how he thinks it should operate. He insists on the minority faction have input. In his thinking, this is how democracy is supposed to work, and the way to keep political disagreements from fracturing society. To him, the notion of one party steamrolling the other is anathema.

But this cuts both ways. Obstruction by the minority faction also is undemocratic, aggravates political divisions, and prevents the Senate from functioning. Thus, while Manchin insists on retaining the filibuster to ensure the minority has a say, he won’t acquiesce to using it as a weapon of obstruction. Besides wanting to make it harder and “more painful” to use, he’s willing to overcome stonewalling by going around it.

Thus, he’s open to using reconciliation to pass bills, saying, “I will change my mind if we need to go to a reconciliation to where we have to get something done once I know they have process into it” (emphasis added). In other words, if they’ve had their say, and they’re blocking “something we have to get done,” he’s prepared to go forward without them.

This is what happened with the Covid relief bill. Biden met with 10 GOP senators who presented him with a take-it-of-leave-it proposition they knew he and his party wouldn’t accept. In the Senate, Manchin pushed his fellow Democrats to give a little on unemployment benefits, i.e. lower benefits for less time, but even so remained closer to the Democratic position than the Republican position on that issue; and he didn’t give in to the Republicans at all on the overall size of the package — sticking with Biden’s $1.9 trillion — or such contentious issues as the GOP’s bitter opposition to aid for state and local governments.

(A USA Today article here sheds light on this otherwise mystifying recalcitrance: Republicans, angry that “blue states” prioritized saving lives over saving business profits by imposing lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates, are determined not to “reward” those policies by making good the tax revenue losses they see as resulting from those policies.)

Manchin also diverged from the Democratic majority’s position on a $15 minimum wage, but that issue didn’t come to a head, because the Senate parliamentarian stripped it from the Covid relief bill, so senators didn’t have to vote on it. Here again, Manchin didn’t embrace the GOP position, but sought a compromise that somewhat took into account their views.

Simply put, Manchin is focusing on the process of legislation, not just what comes out of that process. He’s not a Republican in Democratic clothing, but he has to get re-elected in a red state, and he can’t afford to look like a Democratic rubber-stamper. This probably has a lot to do with why he, more than any other Democratic senator, is insisting the other side be allowed to participate and be heard. Many of the other Democrats in the chamber, having been steamrolled and shut out by the Republicans when they had the majority, are less accommodating. But he broadly supports the Democratic agenda.

And Manchin isn’t blind to reality. He’s keeping his options open. “Let me say this: I’m not willing to go into reconciliation until we at least get bipartisanship or get working together or allow the Senate to do its job,” he said. “There’s no need for us to go to reconciliation until the other process has failed. That means the normal process of a committee, a hearing, amendments, Chuck. And that’s where I am.” (Emphasis added.) And when it has failed, as it inevitably will, on such issues as voting rights and civil rights?

Biden, who also opposes eliminating the filibuster but is open to tinkering with it, probably was speaking for Manchin as well when he said, “It’s going to depend on how obstreperous they become. … I think you’re going to just have to take a look at it.”

In that regard, keep in mind this: Although the Senate is evenly divided, the GOP Senate faction is not representative of America at large. The 50 Republican senators were elected with 40 million fewer votes than the 50 Democratic senators. It’s one thing for the minority to force changes to legislation, especially when public opinion is closely divided. But when a minority faction leverages the process to block legislation with strong public support, that’s borderline tyrannical in nature.

Manchin is simply hewing the line between one and the other. That’s a thoughtful approach, respectful of our democratic ideals, and arises from principled rather than cynical motives. However impatient liberals may be with Manchin’s stance, the impediment to legislating is not his insistence on a bipartisan process that seeks out a midde ground, but the absence of senators like him on the GOP side.