This article contains news and commentary.

This article contains news and commentary.

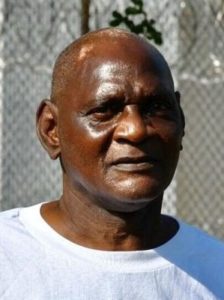

Fair Wayne Bryant, 63, was sentenced to life without parole in 1997 after being convicted of stealing “hedge clippers from a residential garage.” Despite imposing that sentence, Louisiana has decided to parole him, after 23 years in prison for that crime. Read story here.

Did he really get life for stealing hedge clippers? CBS News noted, “While the crime itself did not warrant the life sentence, his four prior felony convictions — an attempted armed robbery, possession of stolen goods, attempted forgery of a check, and simple burglary — triggered Louisiana’s habitual offender statute.”

Also, Bryant didn’t just steal hedge clippers; he entered a residence to steal them. The crime was burglary, a crime that always carries an implicit danger of violence to an innocent homeowner or occupant; the value of the items taken is almost immaterial. If he had shoplifted the hedge clippers from a hardware supply store, that would’ve been a misdemeanor, and wouldn’t have trigger the statute.

Under habitual offender laws, also known as “third strike” laws, offenders who’ve committed three serious crimes can be locked away for good. These laws became popular based on data showing a small percentage of so-called “career criminals” were responsible for a large proportion of total crimes, at a time when drug use fueled a surge in theft-type crimes.

These laws are based on an assumption: That repeat offenders will commit more crimes. In sort, they attempt to predict the future. The public supported the concept in the belief that crime couldn’t be brought under control or communities kept safe except by removing these habitual criminals from society. Also, many people were frustrated by news reports of “revolving door” criminals who served brief sentences and then went back to their criminal ways when released.

In our legal system, a defendant’s prior record isn’t relevant or admissible for determining guilt or innocence, but can be taken into account in sentencing; and having a prior record often causes judges to impose stiffer sentences. When Louisiana’s supreme court upheld Bryant’s sentence, the chief justice argued it was “grossly out of proportion to the crime” and served “no legitimate penal purpose,” but this overlooked the fact that Bryant was a menace to society and likely to commit more crimes, and possibly more serious crimes, unless taken off the streets.

But three-strikes laws have come under growing criticism because of both their harshness and a perception they’re applied in a racist manner. The last thing we need is to give our racially troubled criminal justice system another means of oppressing black people. But the CBS News story about Bryant doesn’t give any clues about whether race was a factor in his sentence or whether the law was misused in his case. He isn’t innocent; he admits having a drug problem at the time.

Instead of looking at these laws as a black-white issue, we should be asking whether the assumption underlying them — that serial offenders will continue offending ad infinitum– is valid. That’s very questionable. Youthful lawbreakers often outgrow that behavior as they age, and people can turn their lives around. The real question in Bryant’s case is less his original sentence and more about whether he can return to society and be law-abiding from now on. He was in his 30s then; he’s in his 60s now, and returns to society in different circumstances. If his drug is behind him, there’s a good chance his past criminal ways are, too.

I don’t want people breaking into my home to steal, and possibly do me bodily harm. I don’t want habitual criminals running loose in my neighborhood. Keeping them locked up as long as they’re a menace makes sense. So I’m prepared to support enhanced sentencing or something akin to involuntary commitment for habitual offenders, if the laws themselves and their administration aren’t tainted by racism, which is unacceptable to me. But for life? For crimes less than murder? That may be overkill. Maybe a better answer is locking them up until they reach a certain age, or easing back into society those who are ready to live crime-free lives.

It’s a complicated problem, and I don’t have simple answers. But I suspect there’s room for improving on the system that locked Bryant away for 23 years for his fifth felony.