Yes, says Lee Drutman (bio here), at FiveThirtyEight. And he’s not even a psychiatrist.

For those watching today’s partisan warfare — Mitch McConnell, when he became Senate Majority Leader, famously declared his mission was to make President Obama a failure — it may come as a surprise that the Senate, where small-population states are over-represented, became a significant factor in thwarting American democracy only in the last 5 years.

Schoolchildren learn in civics class that each state has two senators. This means California, with roughly 39.5 million people, and Alaska, with about 710,000 people, have two votes apiece in the U.S. Senate.

And that means California’s senators represent 55.6 times as many people as Alaska’s senators. Or, put another way, Alaskan voters have 55.6 times as much say in the Senate as Californians do. It doesn’t seem fair, and it certainly isn’t democratic. But that’s our system, and changing it would require amending the Constitution, a practical impossibility (the small states would never go for this).

Yet, surprisingly, Drutman makes a strong case that unequal representation in the Senate didn’t matter for most of American history, because it wasn’t until the parties realigned themselves on geographical and ideological lines (more about that below) that the Senate’s population imbalance became a partisan imbalance — one favoring Republicans and conservatives.

But now, he says,

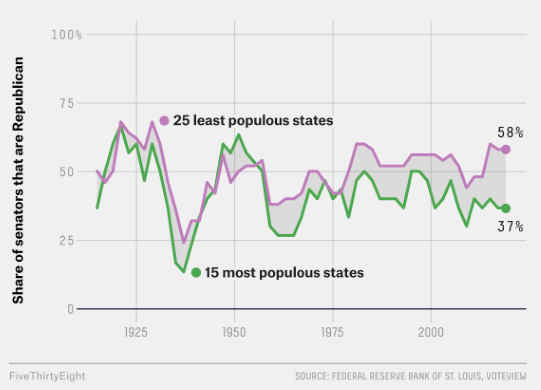

“it’s reached the point that Republicans can win a majority of Senate seats while only representing a minority of Americans. One way to observe this growing partisan bias in the Senate is to compare the party makeup of senators elected to represent the 15 most populous states (which have collectively housed about two-thirds of population since the turn of the 20th century) to the partisan makeup of senators elected to represent the 25 least populous states (which have collectively housed roughly a sixth of the population consistently since the 1960s). As the chart below shows, the partisan makeup of the Senate was fairly even until the 1960s, when Republicans started to amass a partisan advantage in less populated states.” [Italics added for emphasis.]

From this you can clearly see that Republicans didn’t start to get an over-representation advantage until the late 1970s, and it didn’t become pronounced until just a few years ago. To be exact, 2015, Drutman says. As you would expect, that advantage didn’t command liberals’ attention until very recently, because conservatives didn’t have it until then.

From this you can clearly see that Republicans didn’t start to get an over-representation advantage until the late 1970s, and it didn’t become pronounced until just a few years ago. To be exact, 2015, Drutman says. As you would expect, that advantage didn’t command liberals’ attention until very recently, because conservatives didn’t have it until then.

How did this happen? Not all that long ago, both parties had urban and rural “wings,” and “liberal” and “conservative” factions. The realignment over the last few decades, beginning with Nixon’s “southern strategy” in the 1960s, changed that. Now, the Republican Party is unambiguously “conservative” and tilted toward rural constituencies, and the Democratic party is unambiguously “liberal” and strongly identified with urban voters. This urban-vs.-rural divide has become very prominent in American politics; simply put, urban states are Democratic, and rural states are Republican.

This is partly what’s behind the Democrats’ renewed push for D.C. and Puerto Rico statehood, which they assume would give them 4 more senators; although in fairness, they’re mainly motivated by a feeling those U.S. citizens are entitled to the same representation in Congress as the rest of us. (They currently only have non-voting members of the House.) Read Drutman’s article here.

This calculus also is behind a conservative push to break up some states, notably in California, where rural activists have pushed for as many 6 new states. They complain they’re unrepresented by California’s liberal, urban-based senators; but deeper thinkers are well aware that Republicans likely would capture the bulk of these new Senate seats.

This thinking also drives the proposals of some Washington State conservatives to split their state into two, along the boundary between Eastern and Western Washington running through the Cascade mountains. This is also an urban-rural division; the major cities are concentrated in Western Washington. (Eastern Washington has two-thirds of the state’s land area, but only a fifth of its population, and has long complained about Seattle dominating the state’s politics, while accepting generous subsidies from Seattle taxpayers.)

The over-representation of less-populous, more rural states spills over into the Electoral College, too. Here, though, it’s less pronounced, because House districts must have roughly equal populations, and states get 1 electoral vote for each member of Congress (House and Senate combined). It’s still a significant advantage: Alaska has 3 electoral votes, 1 for every 237,000 residents; while California has 55 electoral votes, 1 for every 718,000 residents. If electoral votes were apportioned only for House seats, Alaska would have 1 vote for its 710,000 residents.

Alaska and California, of course, represent the extremes; and the imbalance is smaller when matching other states, but it’s still there.

This advantage sometimes is crucial, because it allows presidential candidates to win while losing the popular vote. That happened again in 2016, when Trump lost the popular vote by 2.9 million votes, yet still won by supplementing his “red state” base with their electoral vote advantage with a few populous “swing” states that Democrats normally are more likely to win.

The 2016 election was not a pure “rural vs. urban” election, because Trump would have lost without urban blue-collar votes in “swing” states, and the 2020 election probably won’t be, either. Political strategists say if he loses in 2020, it will be because he “lost the suburbs,” which are the borderlands between urban and rural America, and the part of America often described as “purple.”

It isn’t just statehood where people are maneuvering for electoral-vote advantages; liberals and progressives are trying to cancel the conservative tilt of the Electoral College by getting enough states to adopt the National Popular Vote Compact, under which participating states would cast their electoral votes for the national winner of the popular vote, to result in direct popular election of the president. Read about the NPVC here. (Comments posted here about NPVC will be considered off-topic; save them for a future article on that topic.)

As for whether the Senate is growing more imbalanced in the sense of unhinged, that’s a matter of opinion, and ultimately is up to the judgment of the voters.

For a long time Senators were not popularly elected. Of course this means State legislatures lost power over Senators, perhaps we should return to that original undemocratic model. Still it is very obvious that in the lead up to the Civil War there was a lot of balancing and trying to keep things on an even keel even if the politics between north and south became more and more imbalanced. The election of 1860 set things on fire as the Senate became out of balance.

The Senate has always been clubby, and individual Senators hold a lot more power than any Representative. Single Senators can put any legislation on hold. Hold up nominations, ect. LBJ got his (well the Republican long sought civil rights bill) civil rights bills and war on poverty bills through due to the death of a single Senator.

Could it also be the Republicans have tried to be electable across a wider section of Americans than the Democratic party? Could it be that both parties enjoy a monopoly over American politics and like with corrupt Monopolies have and both parties have no incentive to change as the parties enjoy control over their territories and neither is overly concerned with the population in those territories, and both do their best work keeping third parties and independents out with voters in a handful of states usually small ones picking independents or wild cards.

The House imbalance is easily fixed by adding more house members. Maybe Alaska should have 7 house members each representing 100,000 residents…and California would have 395 representatives.