Nashira Priester FACEBOOK

Nashira Priester FACEBOOK

Mississippi’s laws served as a model for those passed by other states, beginning with South Carolina, Alabama, and Louisiana in 1865, and continuing with Florida, Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, Tennessee, and Arkansas at the beginning of 1866.

These codes consisted of special laws that applied ONLY to Black persons. The first Black Codes, enacted by Mississippi, proved harsh and vindictive. South Carolina followed with a code only slightly less harsh, but more comprehensive in regulating the lives of “persons of color.” South Carolina’s Black Codes applied only to “persons of color,” defined as including anyone “with more than one-eighth Negro blood.”

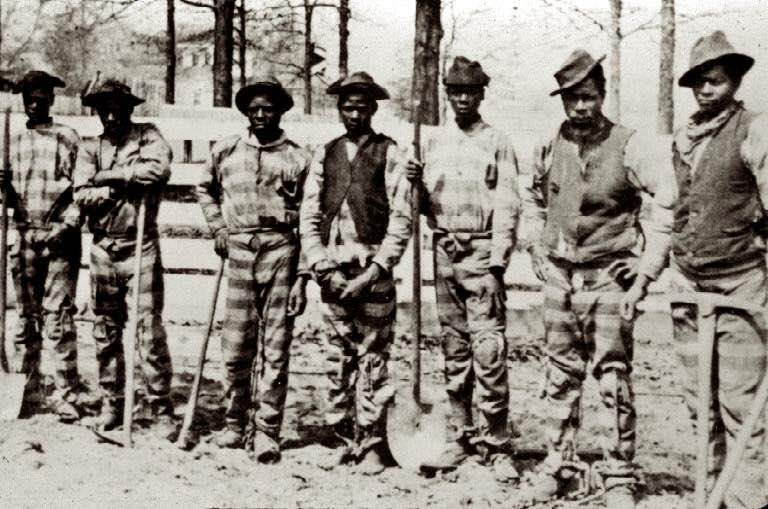

A central element of the Black Codes were vagrancy laws. States criminalized men who were out of work, or who were not working at a job whites recognized. Failure to pay a certain tax, or to comply with other laws, could also be construed as vagrancy. Even states that carefully eliminated most of the overt discrimination in their Black Codes retained laws authorizing harsher sentences for Black people.

Another law allowed the state to take custody of children whose parents could or would not support them; these children would then be “apprenticed” to their former owners. Masters could discipline these apprentices with corporal punishment. They could re-capture apprentices who escaped and threaten them with prison if they resisted.

Other laws prevented Blacks from buying liquor and carrying weapons; punishment often involved “hiring out” the culprit’s labor for no pay.

Mississippi rejected the Thirteenth Amendment on December 5, 1865.

(info: Constitutional Rights Foundation, Library of Congress & The History Channel)