An industry like no other, with profit margins to rival Google

Abstracted from an article by Stephen Buranyi in the Guardian

Abstracted from an article by Stephen Buranyi in the Guardian

….. Scientists create work under their own direction – funded largely by governments – and give it to publishers for free ….. it is as if the New Yorker or the Economist demanded that journalists write and edit each other’s work for free, and asked the government to foot the bill. Outside observers tend to fall into a sort of stunned disbelief when describing this setup. A 2004 parliamentary science and technology committee report on the industry drily observed that “in a traditional market suppliers are paid for the goods they provide”. A 2005 Deutsche Bank report referred to it as a “bizarre” “triple-pay” system, in which “the state funds most research, pays the salaries of most of those checking the quality of research, and then buys most of the published product”.

Scientists are well aware that they seem to be getting a bad deal. The publishing business is “perverse and needless”, the Berkeley biologist Michael Eisen wrote in a 2003 article for the Guardian, declaring that it “should be a public scandal”. Adrian Sutton, a physicist at Imperial College, told me that scientists “are all slaves to publishers. What other industry receives its raw materials from its customers, gets those same customers to carry out the quality control of those materials, and then sells the same materials back to the customers at a vastly inflated price?” (A representative of RELX Group, the official name of Elsevier since 2015, told me that it and other publishers “serve the research community by doing things that they need that they either cannot, or do not do on their own, and charge a fair price for that service”.)

Scientists are well aware that they seem to be getting a bad deal. The publishing business is “perverse and needless”, the Berkeley biologist Michael Eisen wrote in a 2003 article for the Guardian, declaring that it “should be a public scandal”. Adrian Sutton, a physicist at Imperial College, told me that scientists “are all slaves to publishers. What other industry receives its raw materials from its customers, gets those same customers to carry out the quality control of those materials, and then sells the same materials back to the customers at a vastly inflated price?” (A representative of RELX Group, the official name of Elsevier since 2015, told me that it and other publishers “serve the research community by doing things that they need that they either cannot, or do not do on their own, and charge a fair price for that service”.)

In a 2008 essay, Dr Neal Young of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which funds and conducts medical research for the US government, argued that, given the importance of scientific innovation to society, “there is a moral imperative to reconsider how scientific data are judged and disseminated”.

Aspesi, after talking to a network of more than 25 prominent scientists and activists, had come to believe the tide was about to turn against the industry that Elsevier led. More and more research libraries, which purchase journals for universities, were claiming that their budgets were exhausted by decades of price increases, and were threatening to cancel their multi-million-pound subscription packages unless Elsevier dropped its prices. State organisations such as the American NIH and the German Research Foundation (DFG) had recently committed to making their research available through free online journals, and Aspesi believed that governments might step in and ensure that all publicly funded research would be available for free, to anyone. Elsevier and its competitors would be caught in a perfect storm, with their customers revolting from below, and government regulation looming above.

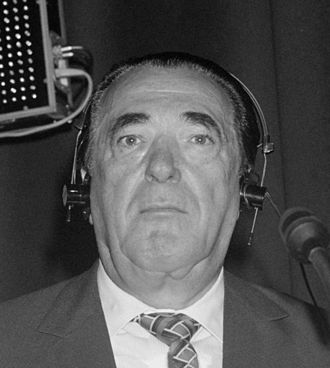

And no one was more transformative and ingenious than Robert Maxwell, who turned scientific journals into a spectacular money-making machine that bankrolled his rise in British society. Maxwell would go on to become an MP, a press baron who challenged Rupert Murdoch, and one of the most notorious figures in British life. . In a 1988 letter commemorating the 40th anniversary of Pergamon, John Coales of Cambridge University noted that initially many of his friends “considered [Maxwell] the greatest villain yet unhung”…………….

Rosbaud, too, was reportedly put off by Maxwell’s hunger for profit. Unlike the humble former scientist, Maxwell favoured expensive suits and slicked-back hair. Having rounded his Czech accent into a formidably posh, newsreader basso, he looked and sounded precisely like the tycoon he wished to be. In 1955, Rosbaud told the Nobel prize-winning physicist Nevill Mott that the journals were his beloved little “ewe lambs”, and Maxwell was the biblical King David, who would butcher and sell them for profit. In 1956, the pair had a falling out, and Rosbaud left the company.

By 1959, Pergamon was publishing 40 journals; six years later it would publish 150. This put Maxwell well ahead of the competition. (In 1959, Pergamon’s rival, Elsevier, had just 10 English-language journals, and it would take the company another decade to reach 50.) By 1960, Maxwell had taken to being driven in a chauffeured Rolls-Royce, and moved his home and the Pergamon operation from London to the palatial Headington Hill Hall estate in Oxford, which was also home to the British book publishing house Blackwell’s.

Scientific societies, such as the British Society of Rheology, seeing the writing on the wall, even began letting Pergamon take over their journals for a small regular fee. Leslie Iversen, former editor at the Journal of Neurochemistry, recalls being wooed with lavish dinners at Maxwell’s estate. “He was very impressive, this big entrepreneur,” said Iversen. “We would get dinner and fine wine, and at the end he would present us a cheque – a few thousand pounds for the society. It was more money than us poor scientists had ever seen.”

Maxwell insisted on grand titles – “International Journal of” was a favourite prefix. Peter Ashby, a former vice president at Pergamon, described this to me as a “PR trick”…… Collaborating and getting your work seen on the international stage was becoming a new form of prestige for researchers, and in many cases Maxwell had the market cornered before anyone else realised it existed. When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first man-made satellite, in 1959, western scientists scrambled to catch up on Russian space research, and were surprised to learn that Maxwell had already negotiated an exclusive English-language deal to publish the Russian Academy of Sciences’ journals earlier in the decade.

“He had interests in all of these places. I went to Japan, he had an American man running an office there by

Cell (now owned by Elsevier) was a journal started by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to showcase the newly ascendant field of molecular biology. It was edited a young biologist named Ben Lewin, who approached his work with an intense, almost literary bent. Lewin prized long, rigorous papers that answered big questions – often representing years of research that would have yielded multiple papers in other venues – and, breaking with the idea that journals were passive instruments to communicate science, he rejected far more papers than he published.

himself. I went to India, there was someone there,” said Ashby. And the international markets could be extremely lucrative. Ronald Suleski, who ran Pergamon’s Japanese office in the 1970s, told me that the Japanese scientific societies, desperate to get their work published in English, gave Maxwell the rights to their members’ results for free.

…………….

Suddenly, where you published became immensely important. Other editors took a similarly activist approach in the hopes of replicating Cell’s success. Publishers also adopted a metric called “impact factor,” invented in the 1960s by Eugene Garfield, a librarian and linguist, as a rough calculation of how often papers in a given journal are cited in other papers. For publishers, it became a way to rank and advertise the scientific reach of their products. The new-look journals, with their emphasis on big results, shot to the top of these new rankings, and scientists who published in “high-impact” journals were rewarded with jobs and funding. Almost overnight, a new currency of prestige had been created in the scientific world. (Garfield later referred to his creation as “like nuclear energy … a mixed blessing”.)

It is difficult to overstate how much power a journal editor now had to shape a scientist’s career and the direction of science itself. “Young people tell me all the time, ‘If I don’t publish in CNS [a common acronym for Cell/Nature/Science, the most prestigious journals in biology], I won’t get a job,” says Nobel winner Schekman.

……………………

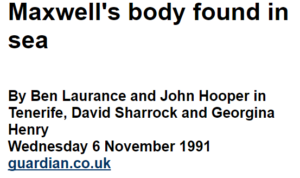

In 1991, to finance ann investment spree in other places, Maxwell sold Pergamon to its quiet Dutch competitor Elsevier for £440m (£919m today). Later that year, he became mired in a series of scandals over his mounting debts, shady accounting practices, and an explosive accusation by the American journalist Seymour Hersh that he was an Israeli spy with links to arms traders. On 5 November 1991, Maxwell was found drowned off his yacht in the Canary Islands. The world was stunned, and by the next day the Mirror’s tabloid rival Sun was posing the question on everyone’s mind: “DID HE FALL … DID HE JUMP?”, its headline blared. (A third explanation, that he was pushed, would also come up.)

In 1991, to finance ann investment spree in other places, Maxwell sold Pergamon to its quiet Dutch competitor Elsevier for £440m (£919m today). Later that year, he became mired in a series of scandals over his mounting debts, shady accounting practices, and an explosive accusation by the American journalist Seymour Hersh that he was an Israeli spy with links to arms traders. On 5 November 1991, Maxwell was found drowned off his yacht in the Canary Islands. The world was stunned, and by the next day the Mirror’s tabloid rival Sun was posing the question on everyone’s mind: “DID HE FALL … DID HE JUMP?”, its headline blared. (A third explanation, that he was pushed, would also come up.)

….. By 1994, three years after acquiring Pergamon, Elsevier had raised its prices by 50%. Universities complained

Despite the backing of some of the biggest funding agencies in the world, including the Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust, only about a quarter of scientific papers are made freely available at the time of their publication.

that their budgets were stretched to breaking point – the US-based Publishers Weekly reported librarians referring to a “doomsday machine” in their industry – and, for the first time, they began cancelling subscriptions to less popular journals. ….. In response, Elsevier created a switch that fused Maxwell’s thousands of tiny monopolies into one so large that, like a basic resource – say water, or power – it was impossible for universities to do without. Pay, and the scientific lights stayed on, but refuse, and up to a quarter of the scientific literature would go dark at any one institution. … Elsevier’s profits began another steep rise that would lead them into the billions by the 2010s. In a 2015 report, an information scientist from the University of Montreal, Vincent Larivière, showed that Elsevier owned 24% of the scientific journal market, while Maxwell’s old partners Springer, and his crosstown rivals Wiley-Blackwell, controlled about another 12% each. These three companies accounted for half the market. (An Elsevier representative familiar with the report told me that by their own estimate they publish only 16% of the scientific literature.)

The idea that scientific research should be freely available for anyone to use is a sharp departure, even a threat, to the current system – which relies on publishers’ ability to restrict access to the scientific literature in order to maintain its immense profitability. In recent years, the most radical opposition to the status quo has coalesced around a controversial website called Sci-Hub – a sort of Napster for science that allows anyone to download scientific papers for free. Its creator, Alexandra Elbakyan, a Kazhakstani, is in hiding, facing charges of hacking and copyright infringement in the US. Elsevier recently obtained a $15m injunction (the maximum allowable amount) against her.

Elbakyan is an unabashed utopian. “Science should belong to scientists and not the publishers,” she told me in an email. In a letter to the court, she cited Article 27 of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, asserting the right “to share in scientific advancement and its benefits”.

Whatever the fate of Sci-Hub, it seems that frustration with the current system is growing. But history shows that betting against science publishers is a risky move. After all, back in 1988, Maxwell predicted that in the future there would only be a handful of immensely powerful publishing companies left, and that they would ply their trade in an electronic age with no printing costs, leading to almost “pure profit”. That sounds a lot like the world we live in now.