from David Preston at the Blog Quixotic

A Leader of Seattle’s Homeless Industry

The Bill Kirlin-Hackett Story

Mr. Mild

The first impression one gets of the Reverend Bill Kirlin-Hackett is of someone we’d expect to find singing kum-ba-ya around the campfire or handing out coffee and hugs at a 12-step meeting. A mild, genial, soft-spoken man in the mellow years, Kirlin-Hackett fits the image of the country parson to a tee. And he uses that impression to great effect, whether he’s meeting in backrooms with legislators or sweet-talking a donation from a church lady. But who is this guy, really?

The first impression one gets of the Reverend Bill Kirlin-Hackett is of someone we’d expect to find singing kum-ba-ya around the campfire or handing out coffee and hugs at a 12-step meeting. A mild, genial, soft-spoken man in the mellow years, Kirlin-Hackett fits the image of the country parson to a tee. And he uses that impression to great effect, whether he’s meeting in backrooms with legislators or sweet-talking a donation from a church lady. But who is this guy, really?

I’ve been following the movements of the Good Reverend – whose name I’ll abbreviate to RBKH from here forward – for several years now on the corruption beat. I’ve encountered him at least half a dozen times testifying at public hearings, asking for government to give more money to advocacy groups and loosen regulations on homeless camps. State legislators tell me that he even writes legislation for them to vote on.

RBKH doesn’t have a congregation or a church. He operates out of rented office space at St. Luke’s Lutheran Church in Bellevue, Washington, from where he runs a small foundation with a big name: the Interfaith Taskforce on Homelessness. The Web page claims it’s a three-man shop, but I’ve never seen anyone besides RBKH representing the group. No one knows how much money RBKH’s charity takes in, or what kind of salary he pays himself out of that. As a faith-based charity, it doesn’t have to make its financial records open to the public.

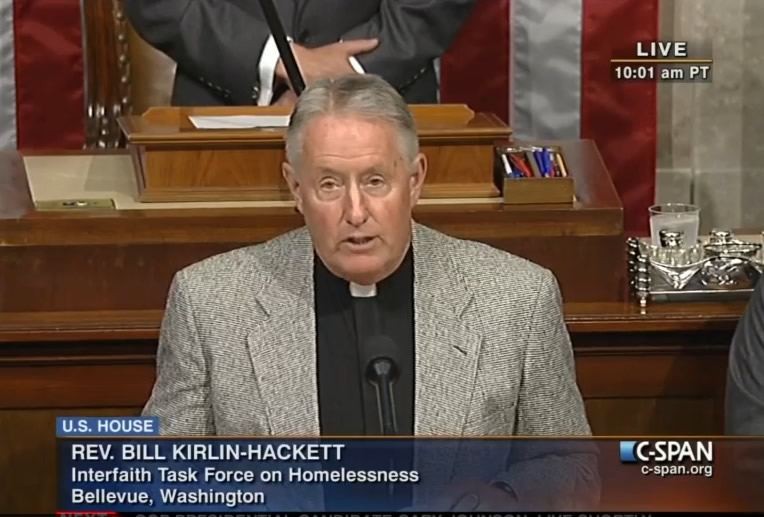

Reverend Bill Kirlin-Hackett leads a prayer in the Capitol Building in Washington D.C.. Image: CSPAN

RBKH could be described as a homeless camp follower. He associates himself with various homeless-related organizations and causes around the county, takes donations, and “advocates” for tent camp operators like SHARE.* At public hearings of the Seattle and King County Council he urges the city and county not to remove illegal homeless encampments. He wants government to be more tolerant of RV campers living on residential streets as well.

He doesn’t appear to do much of anything to get homeless people into permanent housing, though. Nor does he advocate for that. In all of his public comments, I’ve never seen any concrete proposals for moving people off the streets. Strange as it sounds, he seems to be fine with leaving homeless people right where they are.

Being Somewhere

The homeless street newspaper Real Change News regularly carries a guest column by RBKH. His most recent piece is a muddled critique of the Seattle’s decision to step up the sweeping (removing) of illegal homeless camps. Here’s a typical passage:

In a state of emergency, or any emergency, like our house being on fire, we first carry — not sweep — the people to safety. Always. Because that is how we have been trained as “housed people.” When homeless, there’s stuff, possessions and self-worth, from which the person cannot be detached. This stuff gives a sense of belonging. The basic sense of a right to be somewhere. Being. Somewhere. Not just where one can be carried and set down away from the emergency. In a public state of emergency on homelessness, we’d expect to see, among other things, enormous policy changes, innovation and collaboration, such that business-as usual-dissolves. Instead we see what we have seen.

.

Being. Somewhere. A beautiful, worthy dream we can help to make happen. –Reverend Bill Kirlin-Hackett

Don’t push these people off the streets and out of camps, he says, because they’ve got “stuff.” Stuff from which they can’t be “detached.”

Here’s a sample of the kind of “stuff” he’s talking about:

I took the above photo on March 5, at a notorious Seattle encampment called the Triangle, where some 60 people were living. There had been arrests made at the camp several weeks earlier, following reports of a child sex-trafficking ring operating there. (The Triangle camp was swept by the city a week after I took the photo.)

The Triangle was one one of several such camps around Seattle that RBKH had been pressuring the City to keep open. Because the people here have “stuff” he said. Stuff that might get lost if they were placed in shelters or treatment programs. (RBKH isn’t alone in his view of the importance of stuff. See the ACLU’s take on it here and here.)

Contract to Nowhere

In late 2014, the King County government was having trouble with RBKH’s old associate SHARE, so they reached out to him for help. Or perhaps he reached out to them. In any case, given RBKH’s history with SHARE, he was a natural choice. SHARE is a homeless “advocacy” group that, like RBKH, focuses on expanding and normalizing tent camps. SHARE and RBKH go back several years and RBKH was once on the SHARE board of directors.

SHARE had been gaming the County on permit applications for years by letting their permits expire and overstaying their welcome at churches that had agreed to host them. In every case, SHARE knew exactly when their time in the church parking lot would be up; they had months to contact prospective new host churches and set up the next stay. But they didn’t do that. Instead, they would simply run the clock out and overstay their permit until the host would ask them to leave, thus creating a fake eviction emergency that they claimed entitled them to pitch their tens wherever they wish (church land or public land) without getting a “temporary use” permit that everyone else had to.** See a sample of a SHARE pre-eviction press release here.

The County, reeling from bad publicity created by a series of SHARE takeovers of public land, signed a $5,000 one-year contract with RBKH to scout new churches where SHARE and another group (an off-shoot of SHARE called Camp Unity) could set up. His job was simply to call around to churches in East King County that had already hosted a SHARE camp to see which ones would be willing to host another one. He would then work out a “transition schedule” whereby the camps could move in an orderly fashion from one host church to the next, without overstaying their permitted time and without squatting on public land afterward, like they had been doing.

A decrepit RV camper at the 2nd Ave S “Safe Zone” in Seattle’s SODO district. There are three formal, city-funded RV camps around Seattle and dozens of informal ones. Each year, several people living in these contraptions are seriously injured or killed when the propane tanks they use for fuel catch fire. RV camps were just one of Bill Kirlin-Hackett’s many ideas for helping homeless people. Photo: David Preston

But there was a problem. The Reverend had misrepresented himself when he told the County he could bring SHARE to the table. He couldn’t. And he didn’t. Three months after the deal was inked, SHARE moved its Tent City 4 camp once again onto public land (illegally), without even notifying either the County or transition planner RBKH. Once there, they demanded that the land simply be given to them. It wasn’t, but that didn’t stop them for hanging out on it for several months.

In this March 6, 2015 article from the Issaquah Reporter author Daniel Nash quotes a SHARE staffer saying that RBKH was “persona non grata” at SHARE. In the same piece, King County’s Adrienne Qunn says she had urged SHARE director Scott Morrow to work with RBKH but he had refused. (Why the County would have needed to urge Morrow to help a third party fulfill a contract is not addressed.):

Quinn urged Morrow to reach out to the Rev. Bill Kirlin-Hackett of the Interfaith Taskforce on Homelessness to find a hosting church. The Taskforce was hired by the county Dec. 1, 2014 to facilitate locations for encampments, county spokesperson Jason Argo said. But Kirlin-Hackett is “persona non grata” in the SHARE/WHEEL community, according to the organization’s correspondence with Constantine.“I know him and that’s all I’m going to say,” [SHARE staffer Sam] Roberson said [ . . . . ] “To this day he has not approached us.”

But that’s simply not true, according to the reverend. “We reached out to them at least a half-dozen times and they refused our assistance — unceremoniously, I might add,” Kirlin-Hackett said. “They’ve pretty much declined, thinking everyone is just interfering with their process.” Morrow did not answer a question from the Reporter regarding the reasons SHARE/WHEEL did not wish to work with Kirlin-Hackett.

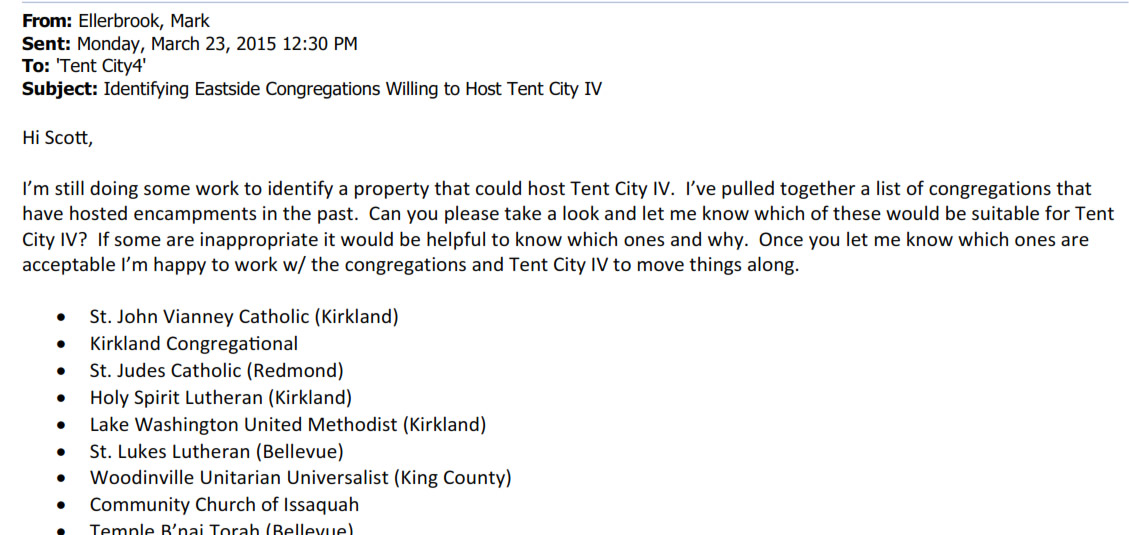

An e-mail chain obtained via public disclosure by Kirkland housewife Janice Richardson shows that by March 23 – less than three months into RBKH’s one-year contract – County staff had already given up on him and were trying to make contacts with SHARE on their own. In the e-mail, County employee Mark Ellerbrook is presenting SHARE boss Scott Morrow with a roster of churches Ellerbrook thought might be to Morrow’s liking. Ellerbrook is saying, in effect: Take your pick and I’ll try to set it up:

In other words, Ellerbrook was doing what the County had already paid RBKH to do.

Regardless of whose fault the breach between RBKH and SHARE was, at this point, RBKH should have returned the $5,000 he’d been paid for the contract, since it was clear he wasn’t going to be brokering any deals for SHARE. But instead, he kept the money. And he spent it. And he didn’t keep records of what he spent it on.

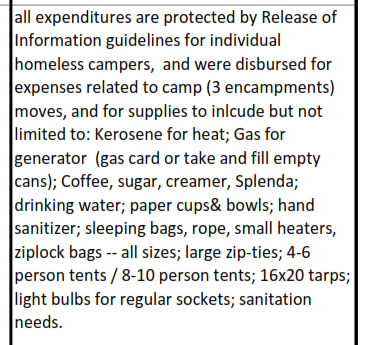

When I learned of the County-RBKH contract, I sent the Reverend a polite letter, certified, inviting him to meet so we could talk about what, if anything, he was doing for the County. That letter is here. RBKH got the letter but didn’t answer. In an e-mail to King County’s Ellerbrook on March 30, 2015, he claimed that he hadn’t gotten any requests from me but wouldn’t respond to them even if he did. He also told Mark Ellerbrook that because I’d written “provocative” e-mails about him to government officials, he was “blocking” e-mail from me.

Don’t ask, don’t tell

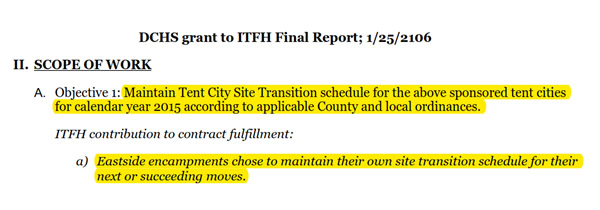

According to contract provisions, RBKH was supposed to submit documentation on contract fulfillment to the County at the end of the contract year (2015). But by the end of January, 2016, he still hadn’t sent anything. When I notified County employee Adrienne Quinn about this, she directed RBKH to assess his own performance and submit any records he had. A week later, he sent his report and Quinn forwarded it to me. In the report he acknowledged, albeit indirectly, that he had failed to provide the primary service he’d been contracted for: making a transition schedule for SHARE and the other camp. He didn’t actually say he’d failed; he simply noted that the encampments “chose to maintain their own schedule” – as if SHARE moving onto public land and squatting there could be called “maintaining a schedule”

I spoke with a manager at the other homeless camp (Camp Unity Eastside) and asked him if Camp Unity had maintained its own “transition schedule” or whether RBKH had helped them do one. The answer: No. –My contact told me that RBKH had bought a couple bus passes for people in the camp and invited them to meet with churches on their own. That’s it, they told me. That’s all he did. –So the Reverend didn’t do anything for Camp Unity either, and unlike SHARE, he was still on good terms with them.

If RBKH didn’t spend the $5,000 making a transition schedule for tent camp, what did he spend it on? Answer: Gas “sustenance supplies,” “office costs,” and a lot of other miscellaneous items that might or might not be related to the work he was supposed to be doing. Here’s another excerpt from his report:

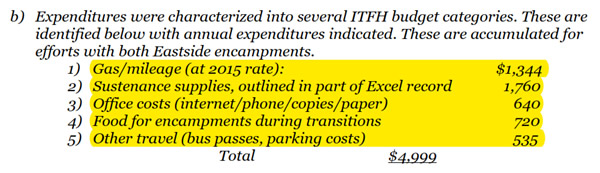

RBKH didn’t produce receipts for any of his expenditures. In the report, he says he outlined (note that word) the “sustenance supplies” in an Excel spread sheet, but the sheet he submitted has no useful detail and can’t be verified. In a note at the bottom, he refers to something he calls the “Release of Information guidelines” as justification for not documenting his purchases:

I asked Ms. Quinn at the County if she’d heard of something called the “Release of Information guidelines.” She hadn’t. After studying RBKH’s report I got back to both Ms. Quinn and King County councilmembers, asking them to apply sanctions against RBKH for not fulfilling his contract duties. They declined. This is a pattern by the County that I will be describing in a series of future posts.

A Law Nobody Wanted

Given the effect homeless camps and RVs have had on the communities of Seattle and King County, one would think RBKH would be the last person whom lawmakers would turn to for advice. Yet in fact he’s one of the first. And in some cases, the only. On November 13, 2014, the Reverend testified before the King County Council, which was then voting on renewing a ten-year homeless encampments ordinance (15170). He told the councilmembers that the existing ordinance was too restrictive. He didn’t like that there was a ban on children at the camps, for example, or that the camp operators were being required to do simple warrant checks before letting someone in. And he especially didn’t like that cities were still being allowed to make permitting rules reflecting what they felt was best for their communities. He wanted the ordinance expanded from unincorporated land to King County as a whole. In his testimony to the County Council, he praised the way Seattle was handling its own homeless program – by expanding church-hosted camps – and said he didn’t want cities and towns to be able to “micromanage them with legislation.” Tent cities are safe and responsible, he claimed. Therefore, they should be encouraged:

At the end of his letter to the C0unty Council, he thoughtfully makes himself available to help the councilmembers “amend what is before them.”

As RBKH was telling the County Council about how safe and responsible SHARE homeless camps were, SHARE itself was already making plans to move its Tent City 4 onto public land. Illegally.

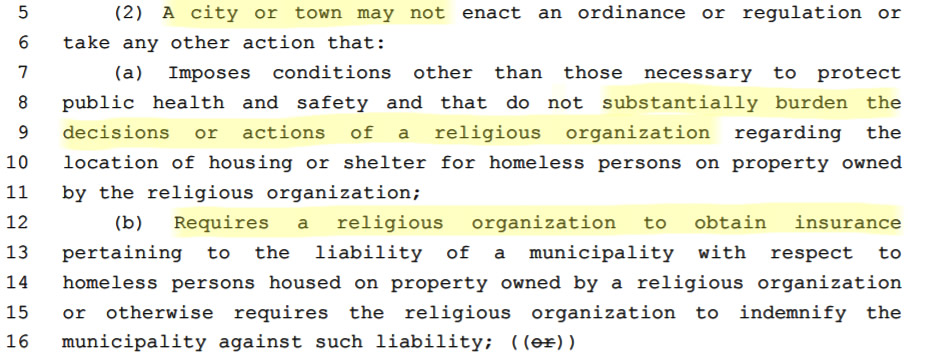

In the end, the King County ordinance passed and RBKH got some of the amendments he wanted. But he didn’t get all of them. After the King County Council balked at imposing an ordinance on the entire county he took his game to the next level: the state legislature. In early 2015, he sat down with State Representative Joan McBride Bellevue (D-Kirkland) to create a statewide bill (HB 2086) that would limit the ability of cities, towns, and counties to regulate homeless camps on church property:

I parsed the bill’s language, and, recognizing some key phrases from RBKH’s testimony at the King County Council and elsewhere, I became suspicious When I asked Rep. McBride about the bill’s provenance, she told me that RBKH had indeed authored it. McBride’s interest in the issue came from her experience with her own church, which had hosted a couple of SHARE’s tent camps. Like the Reverend, McBride felt that the camps were a good thing in and of themselves. She didn’t see them as being a path to permanent housing so much as a place for people to take a break and hang out while they were finding themselves. When I asked if she or other church members spent time with the campers, mentoring them or helping them look for jobs or apartments, she said that wasn’t her purpose. Or the church’s.

McBride feels there should be more camps like the one SHARE had at her church, and she agrees with RBKH that there would be more of them, if only localities could be prevented from over-regulating them. City permitting rules would need to be relaxed, or otherwise gotten around, and a statewide bill could do that. Hence her sponsorship of the bill.

State Rep Joan McBride (D, Kirkland) sponsored a statewide homeless encampments bill in the Washington Sate Legislature in 2015. She told me Kirlin-Hackett wrote the bill.

But was the problem really that cites were micromanaging and over-regulating? Or was something else going on? Some other reason why SHARE has a hard time finding hosts?

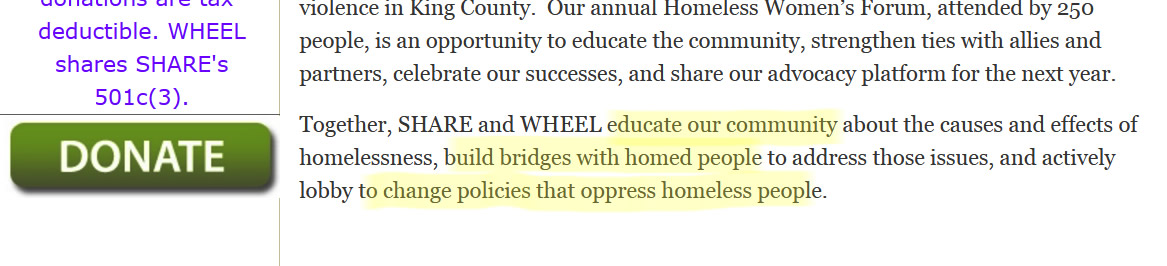

According to what many homeless people have told me, SHARE runs its camps on the authoritarian model, cutting church members out of the process. The group doesn’t encourage long-term mentoring relationships between church members and homeless campers. Like RBKH, SHARE sees itself an advocate, not a housing provider. This screen shot taken from the group’s “About” page is telling:

For their part, campers who want to interact with church members have to tread carefully. When they enter a SHARE camp, they are asked to sign a document acknowledging that they are giving up their Constitutional rights to free speech and association. They’re warned not to complain to the church host about SHARE’s management, on pain of expulsion. In this story about one of SHARE’s church-hosted camps in Seattle, I show how that worked in practice and why it was a problem.

There are problems with crime in around these camps as well, though the church hosts don’t like to admit that, for obvious reasons. But it does explain why many of the choose not to host the camp a second time. When it became clear to King County personnel that RBKH wasn’t going to be able to find SHARE another place to camp, County staffer Mark Ellerbrook began contacting east King County churches that had hosted SHARE camps before to see if any of them would be willing to host again and help the County save face by preventing another occupation of public land by SHARE. Ellerbrook wasn’t having much luck, though. Most churches turned him down with vaguely worded excuses. The pastor at the Woodinville Unitarian Church, Rev. Lois Van Leer, was more direct. In an e-mail response to Ellerbrook, she spelled it out:

Yes, WUCC has hosted Tent City and Camp Unity. We actually hosted Camp Unity for 9 months last year. Their presence did not endear us or them to the neighbors and businesses in the area. There was a huge drug problem that spilled over into the Cottage Lake Park area. We had at least 2 heroin overdoses in camp which the EMTs responded responded to successfully. When folks were barred from the camp, they took up residence and drug use in the park across the street and littered it with needles. They also consumed alcohol there. My understanding is that they have really cleaned up their act which is great. –Reverend Lois Van Leer

Now consider RBKH’s encampment’s bill again, in context. In February 2015, when the bill was introduced, there were just two church-hosted tent camps in King County, and both were having trouble finding hosts willing to take them a second time. RBKH knew about the camps’ troubles better than anyone, because he’d been hired to solve them. And he’d failed. So if anyone knew the real reason the camps were struggling, it was him. And yet, there he was, telling state legislators that local codes were the problem, urging them to create a new statewide law to solve that problem. It makes no sense.

A group of Bellevue citizens who’d had bad experiences with a SHARE camp in their neighborhood got wind of the 2015 Kirlin-Hacket bill and testified against it at the state capitol in Olympia. Several people, including myself, told legislators that the bill should not move forward until it contained better protections for both campers and neighbors. The group also requested that there be more citizen involvement in crafting the legislation.

The citizen testimony hit home, and HB 2086 died a quiet death in committee. But that wasn’t the end of the story. A year later, the same bill resurfaced as House Bill 2044 (Senate Bill 5657), sponsored again by Ms. McBride in the House and Mark Miloscia (R, Federal Way) in the Senate. This time the bill was introduced through a different committee, possibly so it wouldn’t catch the eye of the Bellevue group. But the group found about it anyway and scrambled to oppose it. (Once again, I was one of the people testifying against the bill.) The bill was once again defeated, largely on the strength of our testimony. But who can saw whether we’ll be there to catch it the next time?

The bill will be automatically re-introduced in 2018.

The Reverend Bill Kirlin-Hackett testifies for the second time on a statewide homeless encampments bill he authored. The bill would have restricted the ability of cities and counties to regulate church-run homeless camps.

Reverend without a cause?

Even if the Kirlin-Hackett bill eventually passes, there won’t be a rush of churches wanting to sign up to host a camp, for reasons I’ve explained above. Some churches might be willing to step forward now – even without a state law limiting local permitting requirements – but not if it means having to deal with SHARE. RBKH knows that. He knows the problem is SHARE and not the law. So why does he persist? And why does he continue to maintain that the priority is to expand homeless camps and urban RV camping, when that policy is so clearly a failure?

Perhaps he really thinks he’s doing God’s work, but how do we reconcile that with the way he misrepresents himself to officials and the public? Why won’t he answer simple questions about how much money he takes in, or how he distributes it? And why does he skulk around, pushing this church encampments bill that neither churches nor homeless people are asking for? That nobody seems to be asking for, in fact, besides himself and SHARE? There must be to the Reverend than meets the eye.

Two years ago, I gave the Reverend a chance to tell his side of the story, but he declined. As he did so, he told me never to contact him again. His parting words to me were an admonition. I’m not a “Mr.” he scolded. I’m a Reverend. And not just any reverend either, mind you. But THE Reverend…

The Reverend Bill Kirlin-Hackett.

Remember that name folks, because you’re going to be hearing it again.

–by David Preston, with research by Karen Morris

Dedicated to Janice Richardson

*SHARE is an acronym for the Seattle Housing and Resource Effort. SHARE is a corrupt organization whose history and relationship to Seattle politics I have explored thoroughly in several blog posts, including this one.

**King County’s Temporary Use Permitting process allows for private property owners to convert their property to a number of different temporary uses that would not normally be allowed under zoning laws. (Examples: a Christmas tree sale on a church lot, a traveling carnival on an unused parcel in the business district.) The process is designed to mitigate impacts to the neighborhood while assuring the safety of those using the property under the new permit. Since hosting a homeless camp involves issues of human health and safety, the County has an interest in requiring churches and private hosts alike (should any come forward) to show that they will make reasonable efforts to assure the campers will be safe and won’t become a burden to the surrounding community. A formal application is required and a fee is usually charged to cover the cost the County incurs in reviewing that application. (For a sample application, go here.) That fee is typically waived in the case of SHARE, and over the course of some 20 years, SHARE has been given tens of thousands of dollars in free permit service.