Are the Historical Karaite Jewish Objections to Hanukkah Still Relevant Today?

In 1979, Hadassah Magazine visited the last remaining Karaite Jews of Cairo, Egypt. The magazine provides this tidbit regarding the shochet of the community, Farag Murad Yehuda Menashe:

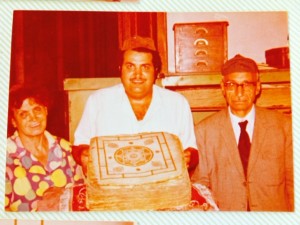

Farag Menashe (still living in Cairo at the time) with the Cairo Codex.

[H]e will read a Haggada based on biblical texts, free of all Talmudic references. He will have no seder plate, no four questions, and no four cups of wine. His Shavuot will always fall on Sunday, and instead of fasting on the Ninth of Av, he will fast on the seventh and tenth. He has never heard the shofar blown, never put on tefillin, and never affixed a mezuzah to the doorpost of his home, and never lit a hanukkiya. (Indeed, Hanukkah is totally absent from his calendar.)[1]

My family, which hails from the Karaite community in Egypt, also never did anything for Hanukkah until coming to the United States. Yes; even Karaites are susceptible to assimilation. Here, we are not simply talking about assimilation toward non-Jews; we are talking about assimilation toward a larger Jewish population within which we are living.[2]

But how is it that this group of Jews did not observe Hanukkah while in Egypt? Let’s examine the two main historical Karaite objections to Hanukkah: (i) the lack of authority to create a religious holiday; and (ii) the victory was short-lived. After each discussion, I’ll let you vote whether the objection is still relevant.

The Rabbis Lacked Authority to Create a Religious Holiday:

The first historical Karaite objection to Hanukkah is rather simple. Historically, Karaites only observed the holidays in the Tanakh. And historically the Karaites rejected the Rabbinic authority to create laws and holidays. An episode from the life of the 10th century Karaite sage Hakham Jacob al-Qirqisani reveals how seriously the Karaties objected to Rabbinic holidays.

Qirqisani asked one of the students of Sa’adyah Gaon why the Rabbanites of his day would marry the Issawites – adherents of a seventh century messianic leader – but would not marry the Karaites. The Rabbanite student’s response was telling: “Because [the Issawites] do not disagree with us over the festivals.”

Kirkisani interpreted the response to mean that the Rabbanites “regard open apostasy [i.e., the Issawite adherence to a messianic leader] more favorably than disagreement [by the Karaites] over a festival of [the Rabbanites’] own invention.”[3] And the Rabbanites acknowledge that Hanukkah (in its religious form) is a completely Rabbinic holiday.

Although the lack of Rabbinic authority to create a holiday is (in my opinion) a completely acceptable basis on which to reject the observance of Hanukkah, the Karaites of the Middle Ages had a problem. As far as I am aware, every Karaite of the Middle Ages held that Purim was a binding holiday. But Purim was not a holiday instituted by God in the Torah. That is, the events of Purim – like the events of Hanukkah – took place well after the Torah was given.

So, how did the Karaites of the Middle Ages believe that Purim was binding but that Hanukkah was not? Some Karaites like Hakham Ya’aqov ben Reuven and Hakham Aharon ben Eliyahu believed that Purim was binding because it occurred during the time of the prophets and was ratified in some way by the prophets:

- And we [too] became obligated and took [the observance of both days of Purim] upon ourselves for this was in the time of prophets and the prophets affirmed [this practice]. However, the Hanukkah that the Rabbanites profess, we have not accepted upon ourselves for this was not at that same time of prophets. Also [although] miracles were performed during each and every era, even those performed in the time of prophets were not [always] set as days for rejoicing and [Hanukkah] is like these [other miracles].- Hakham Aharon ben Eliyahu’s Gan Eden Inyan Yom HaKippurim Ch. 5; Daf 64B Col 1.[4]

For more on whether Purim is binding see my article at TheTorah.com.

A Short-Lived Victory

The second historical reason that Karaites did not embrace Hanukkah is because – at its heart – the miracle of Hanukkah is that the Jews reclaimed that Temple and were able to start worshiping again.

By now, we all know that the story of the oil lasting for eight days does not appear in the earliest sources, and that the first written source to record this is the Talmud (or perhaps earlier rabbinic writings incorporated into the Talmud). If you don’t believe me read someone else’s article on this.

So if the heart of the miracle is that we were able to defeat the Seleucids and reclaim our Temple – Hanukkah itself means “dedication” – then it seems rather ironic to be celebrating the holiday, when we no longer have our Temple.

In this regard, I actually would propose that all Jews who light the “menorah”, refer to it as a hanukkiah. By calling it a menorah, we allow our subconscious to forget that the Menorah – the one in the Temple – is no longer a part of our daily lives.

My Personal Hanukkah Miracle

When I was a sophomore in college, and very much coming into my identity as a Karaite Jew, I first learned that the story of the oil lasting for eight days on Hanukkah was not attested to in any early source. The next year, as a junior, the InterFraternity Conference at the University of California, San Diego scheduled my Jewish fraternity, Alpha Epsilon Pi, to play a football game on the first night of Hanukkah.

Now, as you can infer from this post, I did not have any particular religious connection to Hanukkah. But being one of the most outspoken advocates for the Jewish people in the chapter, I could not in good conscience do nothing. So we organized some brothers to light the hanukkiah on the sidelines of the football game. (The wind ensured that the candles did not stay lit for very long.) I, of course, did not participate in the candle lighting.

Instead, I read aloud during the football game from The First Book of the Maccabees. No joke. I was weird. But I was also trying to prove a point. (In hindsight, I am not sure exactly what the point was. But it definitely made sense at the time.)

Anyway, so as I started to read aloud from Maccabees 1, my very good friend fielded a punt and proceeded to take the ball all the way to the end zone for a touchdown. As my fraternity brothers ran up and down the sidelines pumping their fists, the chapter president grabbed my shoulders and said, “Keep reading!”

You have to understand here. At that time, in the context of IFC football at UCSD, Alpha Epsilon Pi were equivalent to the historical Maccabees trying to defeat a much larger and much more talented fraternity.[5] So, when the president (and others) told me to keep reading, I really wanted to. As an observant Jew, though, I started to become uneasy that some people had superstitiously connected the reading of Maccabees 1 with the mini victory we had on the football field.

Regardless, I decided to read the selections I had marked in my book. I read and read and read. And the more I read, the more we lost. We got crushed in that football game. It was not so much a crushing on the scoreboard; rather, it was that we really could not muster any offense that night.[6] It turns out like the real story of Hanukkah the “victory” we experienced on the football field was also short-lived.

* * *

[1] Rabbi Boruch K. Helman, The Karaite Jews of Cairo, Hadassah Magazine, March 1979.

[2] To be fair, the observance of Hanukkah by most Jews in the United States is not actually a religious observance. It is a secular observance. So, in this respect, the Karaite assimilation towards this Rabbinic custom is also assimilation towards American secularism. But that is a topic for a different day – and probably for someone else’s blog.

[3] See Heresy and the Politics of Community: Jews of the Fatamid Caliphate, Marina Rustow, pp. 63-65 (interpreting the response to refer to the addition ofYom Tov Sheni); see also Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar 2nd Century BCE – 10th Century CE, Sacha Stern, pp. 19-20 (interpreting the response to refer to either Yom Tov Sheni or Hanukkah, “both of which the Karaites rejected but which the [Issawites] might have observed).

[4] I thank Tomer Mangoubi for this translation, which appears in Chapter 23 of Mikdash Me’at, in its section on Oaths. See also Zvi Ankori’s Karaites in Byzantium, in which he records a line from Hakham Ya’aqov ben Reuven’s Sefer Ha’Osher that also states that Hanukah was not binding because of the lack of prophecy at the time.

[5] As I write this, I see the irony of posting about the historical significance of Hanukkah – fight against Hellenization – while touting struggle of my Greek-lettered organization to find a way to signify Hannukah. But I am a huge fan of the work of Alpha Epsilon Pi. So much so that my first job out of college was working as a traveling consultant for AEPi – making $1000 a month. (Yes; you read that right.)

[6] Before anyone starts the “Jews can’t play sports” jokes. I’ll just add that a few years later, Alpha Epsilon Pi won IFC football. The whole thing. Not just a game.