I was surprised one day as I sat in the courtyard, moping over my text, to see my friend Juana come tentatively into the yard bearing a little covered stainless pot, the kind you might see on a hospital tray.

Juana was my cook last year and though she spoke zero English, and I no Kreyol, we communicated, and she showed kindness to me when I was sick. Her demeanor around me was always submissive with a shy but charming smile.

However, I’d watch her on the boat sailing to the market at Madame Bernard across the island and she was anything but soft spoken. Instead, an outspoken force as we floated along in the light airs as conversations got loud and hilarious. (I was grateful–for once they weren’t laughing at me).

She shopped for me occasionally in the noisy market stalls; she demanded and got her price or walked away. I paid no gringo price when she was around.

This day, in this different place, she’d brought me a kettle of fried fishes. The Lavaschwaz have no refrigerators, so they scrub the gutted fish with salt, wash them well with key lime juice and water, repeat, and fry. They’re saltiness does double duty as a preservative–they keep for days–and god knows you need your salt in this climate.

I ate them over the next few days and walked over to her house on Christmas Eve to return the dish, clean of course–I know my manners. I met her husband, Maxim, for the first time–he speaks a little English–and translated her invitation for me to come to dinner the next day.

Wow. An invitation to a Haitian Christmas dinner! I know little about their Christmas traditions, and when I’ve asked, the most common answer is, ‘I eat goat.’ For me, mister rich guy, if it’s goat, it must be Tuesday. I felt good about it, though.

So come the annoited hour, I put on my good shirt (the one with the buttons) a pair of long pants, and trudged through the jungle and over the hills past boys kicking a plastic bottle around like a soccer ball, a girl flying a kite made from a plastic bag with a tail of toilet paper.

Stylishly late by 31 minutes, arrived at the house of Juana and Maxim, and their stair-stepped kids, ages 15, 12, 9, and 3.

Juana wasn’t there, only Maxim and another guy named Fedelhomme (rhymes with bedlam). Maxim said she was just up the path, offered me a chair, and we waited for a time on the high porch, the three of us trying to make bilingual conversation, the way you do.

Juana finally arrived, greeted me with the cheeky cheeky air kiss, air kiss, then darted into the darkness of the house; I could hear her rattling around, pots and dishes, a chair scraping.

Then her voice from inside; Maxim said, ‘She say come.’ I pushed back the scrappy curtain, and went inside.

Houses of the Lavaschwaz are usually dark. There’s no electricity here, and the more fortunate have solar panels, though hundreds of those were lost in the hurricane. If Juana and Maxim had every had solar, they didn’t now.

The main house was three rooms: the master bedroom, the eating room, and a play area with roof but open windows and a floor of smooth white stones. Good for a toddler. There must have been another building or tent out back for the boys to sleep.

The table had a cloth and three large plastic mesh covers, protection from flies. Juana sat me down in front of the red one, and lifted it up revealing a modest pile of rice, and a soup bowl nearly full of sos pwa, the dark, smooth sauce of the inevitable fresh Haitian beans.

Ah, I said, to myself. The first course! Juana sat down across from me and watched as I helped myself to the rice, then flooded my plate with the sos. I greedily ate with a big spoon.

As I ate, the suspicion grew that this was the only course. Christmas dinner? Where’s the goat?

I was effusive with my ‘ah, bon, bons!’ as I wiped my chin with the clean cloth she gave me.

The rice was plain, but the sauce was smooth, complex, and spicy with cloves. Juana is an excellent cook. I could have eaten the whole bowl as a soup which I do if I’m paying for it, but in this situation, I ate as Haitians eat, flooding my plate of rice with it.

I finished, and she tucked what I hadn’t eaten underneath the blue fly cover, and I was left with the feeling I’d eaten a portion that another mouth in the house would be denied.

It felt like shit. No comfort, no joy.

She offered water, and poured me a jelly glass. All water now must be bought and hauled from the mainland since the storm inundated the Kai Kok’s deep well with seawater and sewage. A precious, commodity. I drank small.

That was it. I sat, I ate, she watched. Maxim stayed outside, I never saw a kid. My fantasy of a big table and plates of goat, salade for everyone and laughing and singing and dancing was just that, a fantasy.

I gave her a couple of the flashlites I brought and Tylenol and some blister packs of water purification tabs.

I felt like bwana handing out beads and trinkets.

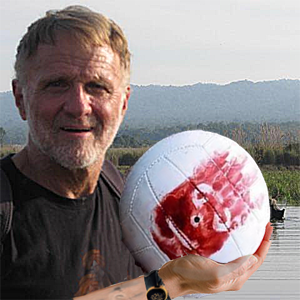

Then we said our awkward goodbyes on the porch. Mwa mwa, mwa mwa. I took a picture of the two of them, and ambled toward home feeling wretched.