Even more significant, it found that six out of ten Jewish children live in Orthodox homes, largely because the Hasidim have very big families (seven or eight children are not uncommon). Jews of no religion (“nones”) are the second largest group in New York. The numbers of Reform and Conservative Jews in the area totalled 583,000 — 80,000 less than ten years before.

(Huffington Post, Sandy Goodman)

57 percent of Orthodox Jews prefer Republicans and the OJ Families Are As Large a Catholic Families were a Century Ago!

The American Jewish community is coming apart at the seams. Its vital center is collapsing, and the entire group is increasingly polarized by runaway growth at both extremes: religious fundamentalism on one end, secular non-belief on the other. The result is not only bad for the Jews, but bad for the rest of America.

Bad for America because the tiny, six-million-member Jewish community — two percent of the population — has proved one of the most vibrant, creative and useful groups in American life. Its loss would be a loss for the entire nation.

American-Jewish accomplishments are well-known, frequently praised and often resented. They include curing polio, building the A- and H- bombs, and winning more than 15 percent of Nobel Prizes in science.

Jews are ten out of 100 U.S. senators, three of nine Supreme Court justices and the chair of the Federal Reserve and her two predecessors; a third of the Forbes 400’s richest Americans — and many leading philanthropists. Jews built great retail chains like Sears and Macy’s and computer companies like Oracle and Dell.

Jews practically invented Hollywood and established the three biggest broadcast networks. Broadway wouldn’t be Broadway without Arthur Miller, Steven Sondheim and Rodgers and Hammerstein. The New York Times and the Washington Post, were founded by Jews. And on and on.

It’s because Jews are so influential in American life that the disintegration of the Jewish community would surely be hurtful to the nation as a whole. Recent surveys show, beyond a doubt, that this unraveling is taking place.

The most important study was the 2013 Pew Portrait of Jewish Americans, a poll of some 3,500 Jews nationwide. It found that almost six out of ten are intermarrying, including more than seven of ten of the non-Orthodox; more than one-fifth of all Jews don’t believe in God, and two-thirds don’t belong to a synagogue.

Other key findings were that although more than 90 percent say they’re proud to be Jewish, the more than 20 percent who don’t believe in their own religion still identify as being Jewish — but only on the basis of ancestry, ethnicity or culture. More important, the percentage of these Jews of no religion (“nones”), has increased with each successive generation, rising fourfold from only seven percent of those born before 1927 to 32 percent of Jews born after 1980.

The effect of this ballooning number of “nones” on the continuity of non-Orthodox Judaism is devastating. Two-thirds of Jewish “nones” don’t raise their children Jewish. Even more than younger Jews generally, they are less likely to join synagogues or other Jewish organizations, donate to Jewish charities, marry other Jews or raise Jewish children.

“It’s a very grim portrait of the health of the American Jewish population,” says Jack Wertheimer, a professor of American Jewish history. Sociologist Steven Cohen sees “a sharply declining non-Orthodox population in the second half of the 21st century.” Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch goes further, predicting that the existence of so many entirely secular Jews threatens their survival:

Practically none… will have Jewish descendants by the third generation. Centuries, perhaps millenia, of Jewish life in those families will end within the next generation or two, no matter how strongly these Jews profess their Jewish identity, or sincerely want Jewish grandchildren.

The same point was forcefully made by the fictional Lord Sinderby, in the British drama series Downton Abbey. A rare Jewish peer in the 1920s, he hotly opposes his son’s marriage to a non-Jewish girl. “Our family has achieved a great deal,” he says. “And now you want to throw all that away… The second Lord Sinderby [the son] may be Jewish but the third [a grandchild] will not,” because of the (oft-ignored) rule of matrilineal descent.

Such concerns prompted columnist J.J. Goldberg to lament:

[W]e could be at a historic turning point. Judaism probably isn’t at risk but the worldly, liberal Jewry that emerged from the Enlightenment could be. The modern Jewish civilization that produced Freud and Einstein, Roth and Bellow, Dear Abby and Hannah Arendt, Sarah Bernhardt, Estee Lauder, Golda Meir and the Marx Brothers could turn out to be nothing more than a blip in history.

All of American Judaism may not be at risk. But dramatic changes in its character are inevitable, given the fast-growing percentage of the Orthodox. “Once dismissed as relics, they now feel that they are the future,” writes New York Times columnist David Brooks. While the total percentage of Jews in the population has held steady for the past two decades, “Orthodox birthrates in just the last few years have been soaring,”says Sociologist Steven Cohen. “The sky is falling for the rest of the population…Every year, the Orthodox population has been adding 5,000 Jews. The non-Orthodox population has been losing 10,000.”

The increase in the Orthodox Jewish population is especially marked by growth among the young and the ultra-Orthodox. Pew data indicate that 27 percent of Jews younger than 18 now live in Orthodox households — a big jump from the next demographic group, Jews age 18 to 29, only 11 percent of whom are Orthodox.

Of the 10 percent of all Jews who are Orthodox nationwide, only three percent are so-called modern Orthodox — Jews who, while seriously observant, are fully members of modern society. Outnumbering the modern Orthodox two-to-one are the much more fundamentalist and insular ultra-Orthodox, including many Hasidim (“pious ones”), notable for their distinctive dress: men in black hats and suits, whose wives conceal their hair under scarves or wear wigs.

Many of Pew’s nationwide findings reflect those of a 2012 survey of six thousand Jews in the New York City area, home to the nation’s largest Jewish population, conducted by the local UJA-Federation. That Jewish group’s poll counted 1.5 million Jews in the area, an increase of 100,000 in a decade, almost entirely because of a “huge surge” in the Orthodox population, which now numbers one-third of the area’s Jews.

Even more significant, it found that six out of ten Jewish children live in Orthodox homes, largely because the Hasidim have very big families (seven or eight children are not uncommon). Jews of no religion (“nones”) are the second largest group in New York. The numbers of Reform and Conservative Jews in the area totalled 583,000 — 80,000 less than ten years before.

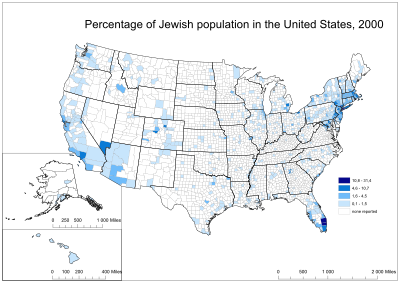

Nationwide, both Reform and Conservative Jews have suffered losses — especially the latter. Reform remains the largest group, at 35 percent. Conservatives are 18 percent. The Orthodox make up 10 percent as noted, and “nones” are another 22 percent.

The changing face of New York Jewry reveals that today’s Jews “are poorer, less educated and more religious” than a decade ago, as well as politically “less liberal” (nationwide, Pew found 70 percent of all Jews favor Democrats, but 57 percent of the Orthodox prefer Republicans). A New York Times story analyzing the local Orthodox surge was headlined: “Are Liberal Jewish Voters a Thing of the Past?”

Not just yet. But the story speculates that “in a generation a majority” of the city’s Jews may be Orthodox, including a sizable number of the ultra-Orthodox Hasidim. An early sign may have been a 2011 special Congressional election in Brooklyn and Queens. A Catholic Republican won a big majority of the Orthodox Jewish vote, beat an Orthodox Democrat and became the first GOP candidate to win the district in 88 years.

Jews who voted for him followed the wishes of their rabbis and other leaders. Ultra-Orthodox Jews often vote as a bloc, following instructions. Undue rabbinic influence and extraordinary community pressure sometimes even cause the ultra-Orthodox to shut their eyes to grievous sins. The New Yorker reported the case of a Hasidic man in Brooklyn who became an outcast by telling authorities about a serial child molester, a prominent member of the community, who sexually abused the man’s son.

The ultra-Orthodox are an exception to the typically high educational levels of Jews in America. Taught in private religious schools called yeshivas rather than public schools, they mostly study religious subjects with little math and less science. Some Hasidic yeshivas offer no secular education after the fifth grade. Students’ English is often poor, because their first language at home and in school is not English but Yiddish, a German dialect.

One rare yeshiva graduate who decided to go on to college didn’t know the meaning of common words like “essay” and “molecule.” An ultra-Orthodox rabbi warned a reporter friend of mine who asked to interview him that he spoke poor English. “Where are you from?” my friend asked. “Brooklyn,” replied the rabbi, explaining that he was brought up speaking Yiddish.

Lack of adequate secular education makes many Hasidim unable to find good jobs. Coupled with their many mouths to feed, this often leads to poverty. The New York study showed “fast-rising levels of poverty that appear to be unparalleled in recent history.” One-fifth of New York Jewish households were poor in 2012. Eleven per cent were on food stamps. The community with the nation’s highest poverty rate in 2008 was no ghetto or barrio but the Hasidic village of Kiryas Joel in upstate New York.

The insularity and resistance to change of some Hasidic sects and individuals is legendary. A visitor feels “like crossing a border into a foreign country,” according to one observer. In one Hasidic Brooklyn neighborhood, illegally posted street signs urged women to cross to the other side to get out of the way if men approached them.

Some Hasidic men caused disturbances on airplanes recently by refusing to sit next to women that were not their wives on flights. Rabbinical assurances to the contrary, they insisted their religion forbids such closeness with women other than their wives and demanded that the women change seats. One female critic labelled such behavior an effort to have women submit to male dominance in a culture “driven by fear of modern society, rigidity and ignorance.”

In contrast to these religious extremists, modern Jews will likely become more invisible as continued assimilation, intermarriage and secularism cause them to blend further into the American landscape. Attempts to reverse that trend have failed in the past and are unlikely to succeed. One big reason is that irreligiousness is spreading in America generally. In that atmosphere, and with Jews less religious than the Christian majority by such measures as attendance at services and belief in God, reversal hardly appears probable.

Some hail this growing Jewish invisibility. One is Gabriel Roth, an intermarried Jewish non-believer. “For anyone not attached to terrible ideas like racial purity, this is good news,” he writes. “Would it be better if Jews still lived in ghettos?” Roth predicts that “[A]part from the very small Orthodox community, Jewishness will eventually die out as a distinct element in American life, ” conceding: “That will be a real loss. But,” he continues:

[W]e should be realistic about what’s being lost and what isn’t. Here are some of the things I cherish about Jewishness: unsnobbish intellectualism, sympathy for the disadvantaged, psychoanalytic insight, rueful comedy, smoked fish. Those things have been thoroughly incorporated into American upper-middlebrow culture. Philip Roth and Bob Dylan and Woody Allen no longer read as “Jewish” artists but as emblematic Americans; their influence is as palpable in the work of young gentiles as young Jews.

Maybe so. But maybe there’s some special mix of Jewish values that may not survive the blender: a combination of veneration for learning, openness to differing ideas, respect for education, hard work and family, together with a powerful yearning for justice and a readiness to side with the underdog. Of course, none of these qualities is exclusively Jewish by any means. Yet taken together, perhaps fueled by legendary Jewish guilt, they may just add up to a unique amalgam of cherished values — hard for others to match.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews share some, but not all, of these values. Especially missing are the openness to differing ideas and respect for education. College is not encouraged. Furthermore, as Steven L. Pease, a chronicler of Jewish accomplishments in his book, The Golden Age of Jewish Achievement, puts it:

The orientation is inward, toward the individual, the family, and the Orthodox community rather than outward toward the secular world … much more toward a return to the past than a focus on the future.

But if most of the rest of American Jews should disappear before the next century, the majority who remain identifiably Jewish may well be this stubbornly insular fundamentalist remnant, unwilling and/or unable to participate in normal American life and feeling constantly threatened by the outside world. As one young defector from Hasidism put it:

Foreign influences are highly toxic to the Orthodox mindset. Even the smallest crack in the perfectly cultivated shell can cause corrosion throughout the system…[Y]ou need to stifle your children. You need to smother any signs of creativity, curiosity, individuality, and definitely any shred of inquisitiveness they might display. Absolutely no movies, or music or books that are even remotely touchy, and definitely no radio of any kind.

Such an insular culture is difficult to maintain — but often hard to quit. However, unless they break away from it, fundamentalist Jews can hardly be expected to carry on the traditional Jewish task of tikkun olam, repairing the world. But they may be the only ones left to repair an increasingly polarized nation in a badly broken world. And the loss of their efforts would be bad for the Jews. And bad for America.