Part of this argument with my brother Hugh is that he wants to dispute that my grandfather was a rabbi. My brother doubts that Zadi Schwartz was ordained since he did not lead a congregation. Sadly this shows an all too common ignorance of the meaning of the term “Rabbi” and the great thread of Jewish heritage stretching back to the founder of the rabbinic tradition, Hillel the Elder.

Hugh’s ignorance reminds me of a story. Some tears ago critics of Judah Folkman, a colleague in my own field of blood vessel biology, criticized his work .. sarcastically calling him the “son of a Rabbi.” This criticism appeared in the pages of the NY Times. I discussed this with Judah and asked him if he wanted to rebut it. He felt that no purpose would be served by feeding the fire. The sad thing is that those critics never got told of Judah’s pride that he, a scientist, was very much continuing the family rabbinic tradition.

Hugh is ten years younger than I and probably had no conversations about our family history with the people who knew the most, our father Robert, his mom Bubbi Perlmitter or my Dad’s older brother Maury . Bubbi Perlmutter told me that she had hoped that I would be a rabbi in the tradition of my namesake. She was very proud that I was an academic, a choice she saw as part of the family tradition. When our son Hillel was born, she was very proud of that name and called him “my little rabbi.”

Uncle Maury had more to say, relating Rab Schwartz’s role as an inheritor of the tradition of Abravanel. Maury, whom we called “Maish,” told me that Schmuel Schwartz was the heir of the teaching of Isaac Abravanel, the last scion of the great Andalusian family of rabbis.

I asked Maish about the history after an occasion when I heard my father called to the bima, the place where the Torah is read, by the name Rab Ravii ben (son of) Rab Schmoel. Maury explained, that Zaydie Schwartz had the respect due to a a Rabbi .. a learned man with the authority given by tradition and other learned men to interpret Jewish law. My Dad was given that title because he was a learned man in the tradition of his father.

Origins of the “Rabbis.”

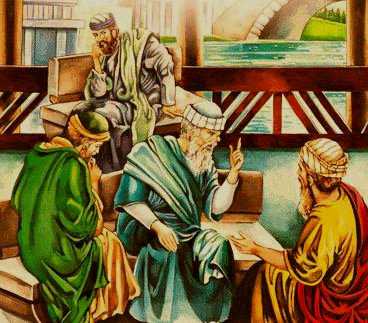

Rabbis did not begin a priests or even as officats of religious ceremonies. They began as leaders of a non violent resistance to Rome. The first Rabbis were the Tannaim,, the scholars, the scribes, described in the Roman Bible, “the New Testament,” as the “Pharissees.” That offensive description reflects the fact the role of Christianity as the mandatory religion f the same Roman Empire, The Tannaim developed under the occupation of the Roman Empire. During this time, the Kohanim (priests) of the Temple became increasingly corrupt and were seen by as collaborators with the Romans. The horrors of the Temple cult and the Roman appointed priesthood needed a response. The Tannaim fought not with swords but with their knowledge of Judaism. This was likely the first efforts at non violent resistance, Hillel is regarded as the greatest of the Pharisees and the founder of the rabbinate.

To the best of my knowledge, Schmoel, at least after coming to the US, never worked as a Rabbi in the sense my brother means. Schmoel was a scholar and teacher in the tradition of the Tannaim (see box), who worked as laborers (e.g., charcoal burners, cobblers) even while studying, teaching and interpreting the law for other Jews. Hillel himself is said to have worked as a cobbler.

As Maury told it , Schmoel also believer in the rabbinic tradition, and refused to earn his living as a Rabbi. My grandfather worked for his living as a roofer. Ironically he fell to his death roofing English High School, the School my Dad and Maury later graduated from.

So, Schmoel was not a rabbi in my brother’s sense of someone who runs a shul, officiates at weddings, provides counseling, or consoles the families of the dead . Rather Schmoel was a Rabbi, who kept the teaching alive and preserved the important writings of Andalusian Jews.

Maury told amazing stories of other Jews gathering at a table in Schmuel’s home, studying the works from Anadalus. Sadly, when Schmoel died, my grandmother lacked the means to preserve the books and writings. Uncle Maury told me that she had given the books, considered holy, to the synagogue in Cambridge for safe keeping. I was able to trace these books through successor synagogues that inherited property as Jews left Cambridge. I got as far as identifying the last synagogue to have the papers. Again, sadly, the synagogue was also closed and all its holy books had been berried in a Jewish cometary in Cambridge. I even found the beadle who must have known where the books were buried in that cometary. By his time however, this last Jew of that story had Alzheimers.