Ancient skeletons show direct link to modern tribes in the Pacific Northwest

Ancient skeletons show direct link to modern tribes in the Pacific Northwest

Scientists sequencing the DNA of 10,300-year-old human sea farers from On Your Knees Cave in Alaska have found that they were closely related to three ancient skeletons found along the coast of British Columbia in Canada. These three ancient people were in turn closely related to the Tsimshian, Tlingit, Nisga’a, and Haida tribes living in the region today.

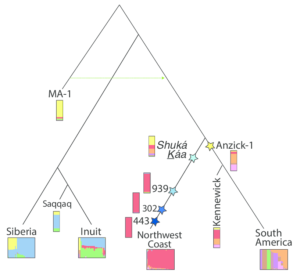

The new finding reveals a direct line of descent to these tribes, and it shows—for the first time from ancient DNA—that at least two different groups of people were living in North America more than 10,000 years ago.

The study started 21 years ago with an unusually friendly collaboration between archaeologists and the Tlingit tribe that lived near the mariner’s remains on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. Researchers gathered DNA from the 10,300-year-old skeleton known as Shuká Káa (“Man Ahead of Us”), initially focusing on maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). They didn’t find a match between its mtDNA and members of the tribe, but they discovered his seafaring ways because isotopes from his teeth showed he ate a marine diet. The project ended on a note of good will between scientists and Native Americans, with a ceremonial reburial of the skeleton in 2008.

But as methods of sequencing ancient DNA got exponentially better, the team of geneticists requested permission from the Tlingit and Haida of Alaska, as well as tribes farther south in British Columbia, to extract nuclear DNA from Shuká Káa and three other ancient skeletons. They were allowed to sample the last remaining tissue from Shuká Káa’s molars and from the teeth of a 6075-year-old skeleton on Lucy Island in British Columbia (just 300 kilometers from On Your Knees Cave), a 2500-year-old skeleton from Prince Rupert harbor in British Columbia, and another 1750-year-old skeleton from the same area.

Although Shuká Káa’s DNA was too damaged to sequence his entire genome, a team led by molecular anthropologist Ripan Malhi from the University of Illinois in Champaign was able to sequence markers that represented about 6% of his genome. (They also sequenced one-third to two-thirds of the genomes of the other three individuals.) The team then compared those markers to see how closely related the ancient individuals were to each other and to 156 indigenous groups living around the world today. They found that genomewide sequences from the three most recent remains from Lucy Island and Prince Rupert harbor off the coast of British Columbia were closely related to the Tsimshian and other tribes in the Pacific Northwest.

This cast of a jaw comes from a 10,300-year-old ancient human who may have been an ancestor of modern tribes in the Pacific Northwest. Courtesy E. James Dixon

Shuká Káa, on the other hand, appears more closely related to groups living in South and Central America today, such as the Karitiana, Suruí, and Ticuna of Brazil’s Amazon. But the signal is not statistically strong, and it may simply be a sign that the tribes all share DNA from the same ancient ancestors in Asia or Beringia where humans lived before they entered the Americas. But Shuká Káa’s maternally inherited mtDNA and nuclear DNA both suggest he is also close kin of the younger skeletons in the study. Connecting the dots between all the ancient individuals, Malhi’s team proposes that Shuká Káa is also ancestral to all those groups, including the Tsimshian and related tribes in the Pacific Northwest, they report today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences early edition.

In another interesting twist, the team found that the group of skeletons was not closely related to two other famous Paleoindians: the 8545-year-old Kennewick Man, unearthed from the banks of the Columbia River in Washington state, and the 12,600-year-old Anzick child from Montana. This suggests there were at least two groups of settlers who came to North America across the Bering Strait land bridge before 10,000 years ago, Malhi says. Although multiple migrations have long been documented, this is the first ancient DNA evidence of different groups arriving in North America at such an early date.

Other researchers call the link between the three more recent skeletons and the tribes of the Pacific Northwest “quite clear.” Paleogeneticist Pontus Skoglund of Harvard University, who was not involved in the work, says support for those tribes’ relation to Shuká Káa is weaker, but possible. It could also be, he adds, that Shuká Káa was alive before the lineage formed that led to current northwest groups.

Whether the ancient mariner is a direct ancestor of today’s tribes or not, the discovery of the link from the recent skeletons fits with Tlingit and Tsimshian oral traditions that suggest the Tsimshian migrated west along British Columbia’s Naas River to the coast, before spreading north and south, says Rosita Worl, president of the Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau and a member of the Tlingit tribe. Archaeologist Timothy Heaton of the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, whose team discovered Shuká Káa, adds that the genetic links fit with the engraving the Tlingit put on the headstone when they reburied Shuká Káa: “We Have Lived in Southeast Alaska Since Time Immemorial. Shuká Káa is Testimony to Our Ancient Occupancy of This Land.”