A bit of UW history that has yet to be told.

Back during the McCarthy era, the House Unamerican Activities Committee worked with the far right government of South Korea to pursue Koreans who stood for democracy. That pursuit extended even to the US where the Korean spy agency worked to deport political refugees so they could face Fascist justice at home. Some of these patriots, facing imprisonment or death at home, fled to the US.

Johsel Namkung was Born in Gwangju, Korea in 1919 where he grew up with a love for both art and music. He studied voice at The Tokyo Conservatory in Japan, and in fact, won the All-Japan Music Contest in 1940. Following the war, Johsel and his wife Mineko came to Seattle when they received scholarships to the University of Washington School of Music. After receiving a Masters in Music at UW, Namkung worked for Northwest Airlines, who hired him because he spoke fluent Korean, Chinese, and Japanese. But in 1956, his love for photography caused him to leave Northwest to study photography and print making full time. His studies included apprenticeships, work in commercial studios, and a week-long workshop with Ansel Adams in 1958. Namkung was a member of the Seattle arts community and was close friends with artists George Tsutakawa, Mark Tobey, and Kenneth Callahan, among others. Namkung worked for 25 years as a medical photographer at the UW Medical Center, a job that gave him plenty of free time for his nature photography. The UW’s Henry Art Gallery held several solo exhibitions of Namkung’s photographs (1966 and 1973). The Seattle Art Museum held its first Namkung show in 1978, and another in the summer of 2006 at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. Namkung’s photos are in the collections of the Seattle Art Museum, the Oakland Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Henry Gallery. The Allen Center holds two photographs from the 2006 Seattle Art Museum exhibit on the 2nd and 4th floors. Johsel Namkung died in 2013 at the age of 94.

One of these Korean refugees was a young opera singer, Johsel Namkung. Johsel and his wife Mineko had come to Seattle to pursue degrees in music. Johsel’s goal was to sing German Lieder.

In addition to Johsel’s magnificent voice, he was a photographer. Johsel became a friend of the Seattle Four, including Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, and Guy Anderson. Others whose work from this era blended the mystic light of the Northwest with Asian art traditions included Johsel’s friends, George Nakashima, Paul Horiuchi, and George Tsutekawa.

I was lucky enough to meet Johsel when I was a graduate student in Pathology at the UW. Johsel and Mineko were were targeted by HUAC because of his politics. HUAC tried to get the Namkungs deported, using the excuse that they had overstayed their visas to earn degrees at the UW.

My mentor, Earl Benditt, came to Johsel’s relief. Earl, the founder of the UW’s program in Experimental Pathology, had recruited Ed Smuckler who worked on liver disease as well as Russel Ross and myself to work on blood vessels. The three of us were among the first to use the electron microscope to explore tissue at the level of cell organelles. Earl’s vision was that we needed a master photographer to print the images from what he called “the big eye.” With Earl’s support, Johsel created a state of the art photo lab in the Department of Pathology.

The UW Pathology Photography Lab went far beyond the capacity needed for electron microscopy .. it allowed

Since 1965, I have developed a different way of seeing things. I am not interested in photographing the things that delimit one’s inner vision. For example, I avoid including the sky because it reveals the identity of the place. The horizon and ridge lines will give you ready answers. I like to give my viewers questions, not answers. Let them find beauty in the most mundane things, like roadside wildflowers and tumbled weeds. Observe the essence of things. That’s Zen. It doesn’t have to be some spectacular manifestation of nature.

My attitude of photographing is very, very serious. The act of selecting a subject to photograph is time-consuming. After the final selection of the subject, determination of exposure needs equally critical attention. I cannot approach the whole process haphazardly. The act of creative execution is not unlike performing music on the stage. You cannot sing three times and tell the audience to select the performance they like best. My negatives are my definitive statement and they need not be cropped or altered. At least that is what I aspire to.

I spend a lot of time looking for subjects. Oftentimes, I make a scouting trip, hiking for instance, going up a trail to a certain point. I usually leave my camera equipment behind, and hike and scout and come back, and if it’s worthwhile, I then take my camera up, and spend a long time adjusting, setting up, digesting or looking at it, and from different angles, distances, and so forth. And finally, when I find something, there always has to be a unifying, kinetic force. Which means the rhythm, and in musical terms the melodic lines. And polyphonic melodic lines especially, like Bach, for instance, or Handel and Mozart. Linear structures. And then its juxtaposition, its counterbalancing, which is called counterpoint in musical terms. And I find almost every time, when I see something, I always see melodic lines, and counterbalancing forces, and weight, and harmony. And that becomes the skeletal form of my photographs. So my photographs could always be interpreted through musical forms.

My idea has always been that photography should be considered as one of the major arts, not just paintings or sculpture as major art, but photography also. In order to compete for attention with oil paintings and watercolors, I thought photographs have to be about equal size. So that led me to using the large-format camera.

If my 2007 exhibition in Seoul was the climax of my photography career, this book I think of as the denouement. It is a definitive collection of what my publisher and I agree is my best work. And the production has involved my wife Monica, daughters Irene and Poki, their husbands John and George, granddaughter Sara and her husband David. It is hard to imagine a more wonderful way to spend my ninety-third year than continuing my life’s work surrounded by dear friends and family.

— Johsel Namkung, 2012

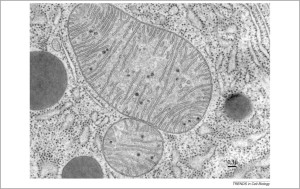

This image, not printed by Johsel, is typical of the electron microscope. Of course, there is no reality here. The image is an interpretation of how a vry thin slice of tissue would look if we could see it in light with light instead of electrons. Making these images real to humans, relies on ideas very much like those of Adams’s zone system.,

Johsel to obtain equipment to create master works of photography. The job, along with help from Hal Green, a civil rights lawyer in Seattle, saved Johsel’s life.

The Pathology Lab might as well have been built on a Steinway classic piano. Johsel’s work built of the rigor of Ansel Adams. Ansel had also begun his life as a classical musician. His intent of becoming a concert pianist ended when Ansel developed rheumatoid arthritis. Although the Adams’s living room had a grand piano, Ansel could make little use of it .. rather he also had a magnificent darkroom in the house on a cliff overlooking Point Lobos.

Adams transferred the musical scales to photography, a discipline called “The Zone System.” Johsel ‘s Photography Lab had the tools to use the “zone system” .. Adams’ ideas about the tonal qualities of a photograph … to create masterpieces of subtlety .. whether these were prints of fatty liver or muted mosses growing on a rock in the Olympic rain forest.

When my wife and I can here in the late sixties, Namkung had already became a hero to many of us who were working in photography. Thanks to the job at the UW, Johsel never had the need to do commercial work. Instead he could explore the tonalities that exist in the forms of lichens growing in rocks or the light falling through our misty skies.

His quietness and vision are a great heritage.

A friend of Johsel’s, Dick Busher . “Johsel Namkung / A Retrospective”. You can see the book at http://johselnamkung.net/ The book has a collection of one hundred exquisite images selected from a remarkable career in photography spanning six decades.

Johsel’s image of rocks and water is, to me, as surrealistic as the image of a slice through tissue.