History records no phenomenon like him. Ought we to call him “great”?

No one evoked so much rejoicing, hysteria, and expectation of salvation as he; no one so much hate. No one else produced, in a solitary course lasting only a few years, such incredible accelerations in the pace of history. No one else so changed the state of the world and left behind such a wake of ruins as he did. … Hitler’s peculiar greatness is essentially linked to the quality of excess. It was a tremendous eruption of energy that shattered all existing standards. Granted, gigantic scale is not necessarily equivalent to historical greatness; there is power in triviality also. But he was not only gigantic and not only trivial. The eruption he unleashed was stamped throughout … by his guiding will. … In fact, to a virtually unprecedented degree, he created everything out of himself and was himself everything at once: his own teacher, organizer of a party and author of its ideology, tactician and demogogic savior, leader, statesman, and for a decade the “axis” of the world. He refuted the dictum that all revolutions devour their children; … he dominated his revolution in every phase, even in the moment of defeat. This argues a considerable understanding of the forces he evoked. … He also had an amazing instinct for what forces could be mobilized at all and did not allow prevailing trends to deceive him. The period of his entry into politics was wholly dominated by the liberal bourgeois system. But he grasped the latent oppositions to it and by bold and wayward combinations seized upon these factors and incorporated them into his program. … One particular source of his strength lay in his ability to build castles in the air with an intrepid and acute rationality. … In spite of the collapse of all his hopes after the attempted putsch of November, 1923, he did not take back a single one of his words, did not mute his battle cry, and refused to modify any of his plans for domination of the world. In those days, he later remarked, everyone had branded him a visionary. “They always said I was crazy.” But only a few years later everything he had wanted was reality, or at any rate a realizable project …. In this ability to uncover the deeper spirit and tendencies of the age, and to represent those tendencies, there certainly is an element of historic greatness. … And yet we hesitate to call Hitler “great.” Perhaps what gives us pause is not so much the criminal features in this man’s psychopathic face. For world history is not played out in the area that is “the true site of morality,” and Burkhardt has also spoken of the “strange exemption from the ordinary moral code” which we tend to grant in our minds to great individuals. We may surely ask whether the absolute crime of mass extermination planned and committed by Hitler is not of an utterly different nature, overstepping the bounds of the moral context recognized by both Hegel and Burckhardt. Our doubts of Hitler’s historic greatness also spring from another factor. The phenomenon of the great man is primarily aesthetic, very rarely moral in nature; and even if we were prepared to make allowances in the latter realm, in the former we could not. An ancient tenet of aesthetics holds that one who for all his remarkable traits is a repulsive human being, is unfit to be a hero … this description fits Hitler very well … his unmistakably vulgar characteristics give his image a cast or repugnant ordinariness that simply will not square with the traditional concept of greatness. “Impressive in this world,” wrote Bismarck in a letter, “is always akin to the fallen angel who is beautiful but without peace, great in his plans and efforts, but without success, proud and sad.” If this is true greatness, Hitler’s distance from it is immeasurable. — Joachim Fest

Readers who want to understand the Nazi phenomenon and its role in history often turn to William Shirer’s iconic book, “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.” Joachim Fest’s “Hitler” is less well known to Western readers, but more trenchant and searching, and more focused on the man than the cataclysmic events he set in motion. Shirer’s account is history; Fest’s is, to a degree, psychoanalysis — of a leader and a society. Fest, as the above excerpt from his prologue addressing the question of what constitutes historical greatness reveals, also delves into how we react — intellectually and emotionally — to history-moving leaders and their movements when we are passive observers.

William Shirer (1904-1993) was an American journalist and war correspondent who lived in Berlin and reported from there during the years of Hitler’s rise to power. He was “embedded” with the German forces during the blitzkreig campaigns of the early stages of the war, before America’s entry into the conflict as a belligerent. By December 1940, his situation had became untenable and he left Germany, returning in 1945 to cover the Nuremberg trials. During his time in Nazi Germany, Shirer watched history being made, and wrote about what he saw.

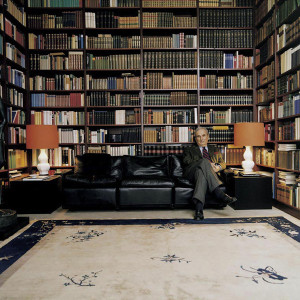

Joachim Fest (1926-2006) was born in Berlin, the son of an anti-Nazi Catholic schoolteacher who was dismissed from his teaching post when Hitler came to power. Fest’s family refused to enroll him in Hitler Youth, resulting in his expulsion from school, so they sent him to a Catholic boarding  school in Baden, a village near Bremen in northern Germany. Upon turning 18 in 1944, he enlisted in the Wehrmacht to avoid being drafted into the Waffen SS, and served only briefly before becoming a POW in France. After the war, “he studied law, history, sociology, German literature, and history of art” (Wikipedia) at a German university, then worked for an American-run radio station in postwar Berlin, which led him into book-writing. Thus, like Shirer, he was essentially a journalist and not an academic historian. Writing as a German who grew up during the Nazi era, but was unsympathetic to the Nazi cause, Fest tackled the story of Hitler “as no non-German could: dispassionately, but from the inside” (Time magazine). While not actually an insider, Fest’s experience included working as an editorial assistant for Albert Speer in writing the latter’s autobiography.

school in Baden, a village near Bremen in northern Germany. Upon turning 18 in 1944, he enlisted in the Wehrmacht to avoid being drafted into the Waffen SS, and served only briefly before becoming a POW in France. After the war, “he studied law, history, sociology, German literature, and history of art” (Wikipedia) at a German university, then worked for an American-run radio station in postwar Berlin, which led him into book-writing. Thus, like Shirer, he was essentially a journalist and not an academic historian. Writing as a German who grew up during the Nazi era, but was unsympathetic to the Nazi cause, Fest tackled the story of Hitler “as no non-German could: dispassionately, but from the inside” (Time magazine). While not actually an insider, Fest’s experience included working as an editorial assistant for Albert Speer in writing the latter’s autobiography.

Wikipedia:

“Fest then embarked on his most important work, his biography of Adolf Hitler, which was published in 1973. This was the first major Hitler biography … by a German writer. It appeared at a time when the younger generation of Germans was confronting the legacy of the Nazi period, and proved to be … immensely influential. … Fest explained Hitler’s success in terms of what he termed the ‘great fear’ that had overcome the German middle classes, as a result not only of Bolshevism and First World War dislocation, but also more broadly in response to rapid modernisation, which had led to a romantic longing for a lost past. This led to resentment of other groups — especially Jews — seen as agents of modernity. It also made many Germans susceptible to a figure such as Hitler who could articulate their mood. ‘He was never only their leader, he was always their voice … the people, as if electrified, recognised themselves in him.’“

Fest’s biography is not a rival for Shirer’s history. The two books complement each other, and with Speer’s “Inside the Third Reich,” these three books constitute an indispensable trilogy for readers seeking understanding of what happened, how it happened, and why it happened. None of this is light reading for people who prefer to think only of happy things. Would that we all could live in a happy world. But we do not. Some of us, at least, must seek out and study the dark things in human nature and in the history our species has created on this planet. If we do not, the danger increases that such things — or worse — will be resurrected by other disruptive social forces and more malevolent dreamers. If we don’t want more Auschwitzes and Buchenwalds, we must grit our teeth and wade into these dark places, and then try to tell the world what we’ve learned.

I read both books years ago and always felt Fest’s was the better book in terms of understanding the Hitler phenomenon. Shirer was a journalist, Fest a historian; Shirer reported what he saw, while Fest explains how and why it happened.