To the student or legislator paying tuition, or the taxpayer funding NIH, it does not matter whether administrators are using their money to pay themselves or increase their staffs,;the difference is a distinction with no meaning. The focus of the public discussiion is always the same … the faculty and are they, the faculty, efficient?

To the student or legislator paying tuition, or the taxpayer funding NIH, it does not matter whether administrators are using their money to pay themselves or increase their staffs,;the difference is a distinction with no meaning. The focus of the public discussiion is always the same … the faculty and are they, the faculty, efficient?

In a remarkable essay, Benjamin Ginsberg an economist at Johns Hopkins, suggests that this is the wrong question. He suggests that the real issue is corporate bloat,. Ginsberg sees the problem with the cost of education as being similar to our national corporate problem where money in the US goes into the handling of money rather than into productive labor. We pay a huge part of our GDP to people who shuffle money, the result is that we are less successful in making stuff then making money. The same appears to be true for how we pay for higher education.

More successful democratic economies, Germany, Sweden and Canada, have dealt with the corporate problem by requiring worker participation in governance. The CEO of Volkswagen needs to get the unions to agree to increase executive pay. Ginsebrg suggests that the answer in academia is to return the faculty to its traditional role in governing the university.

Parents who wonder why college tuition is so high and why it increases so much each year may be less than pleased to learn that their sons and daughters will have an opportunity to interact with more administrators and staffers— but not more professors. Well, you can’t have everything.

But given the general fattening of administrative ranks in recent years, even schools with average administrator-to-student ratios could stand to see major cuts in their administrative staffs and budgets. With fewer deanlets to command, senior administrators would be compelled to turn once again to the faculty for administrative support. Such a change would result in better programs and less unchecked power for presidents and provosts. … Moreover, with fewer administrators to pay and send to conferences and retreats, more resources might be available for educational programs and student support, the actual items for which parents, donors, and funding agencies think they are paying.

(note: AVE figures are based on data abstracted from the article by Benjamin Ginsberg in the Washington Monthly)

Universities are now filled with armies of functionaries—vice presidents, associate vice presidents, assistant vice presidents, provosts, associate provosts, vice provosts, assistant provosts, deans, deanlets, and deanlings, all of whom command staffers and assistants—who, more and more, direct the operations of every school. Any hope of getting higher education costs in line, and improving its quality begins with taking a pair of shears to the overgrown administrative bureaucracy.

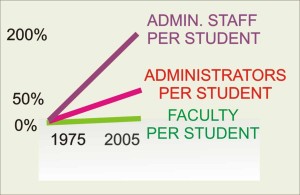

Between 1975 and 2005, total spending by American higher educational institutions, stated in constant dollars, tripled, to more than $325 billion per year. Over the same period, the faculty-to-student ratio has remained fairly constant, at approximately fifteen or sixteen students per instructor. One thing that has changed, dramatically, is the administrator-per-student ratio. In 1975, colleges employed one administrator for every eighty-four students and one professional staffer—admissions officers, information technology specialists, and the like—for every fifty students. By 2005, the administrator-to-student ratio had dropped to one administrator for every sixty-eight students while the ratio of professional staffers had dropped to one for every twenty-one students.

In the 1960s and 1970s top administrators were generally drawn from the faculty, and even midlevel managerial tasks were directed by faculty members. These moonlighting academics typically occupied administrative slots on a part-time or temporary basis and planned in due course to return to full-time teaching and research. Whatever their individual faults and gifts, faculty administrators seldom had to be reminded that the purpose of a university was the promotion of education and research, and their own short-term managerial endeavors tended not to distract them from their long-term academic commitments.

Alas, today’s full-time professional administrators tend to view management as an end in and of itself. Most have no faculty experience, and even those who have spent time in a classroom or laboratory often hope to make administration their life’s work and have no plan to return to teaching. For many of these career managers, promoting teaching and research is less important than expanding their own administrative domains. Under their supervision, the means have become the end.

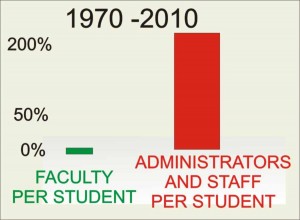

Forty years ago, America’s colleges employed more professors than administrators. The efforts of 446,830 professors were supported by 268,952 administrators and staffers. Over the past four decades, though, the number of full-time professors or “full-time equivalents”—that is, slots filled by two or more part-time faculty members whose combined hours equal those of a full-timer—increased slightly more than 50 percent. That percentage is comparable to the growth in student enrollments during the same time period. But the number of administrators and administrative staffers employed by those schools increased by an astonishing 85 percent and 240 percent, respectively.

Today, administrators and staffers safely outnumber full-time faculty members on campus. In 2005, colleges and universities employed more than

40 Years of Administrative Growth Before they employed an army of professional staffers, administrators were forced to rely on the cooperation of the faculty to carry out tasks ranging from admissions to planning. An administration that lost the confidence of the faculty might find itself unable to function. Today, ranks of staffers form a bulwark of administrative power in the contemporary university. These administrative staffers do not work for or, in many cases, even share information with the faculty. They help make the administration, in the language of political science, “relatively autonomous,” marginalizing the faculty.

675,000 fulltime faculty members or full-time equivalents. In the same year, America’s colleges and universities employed more than 190,000 individuals classified by the federal government as “executive, administrative and managerial employees.” Another 566,405 college and university employees were classified as “other professional.” This category includes IT specialists, counselors, auditors, accountants, admissions officers, development officers, alumni relations officials, human resources staffers, editors and writers for school publications, attorneys, and a slew of others. These “other professionals” are not administrators, but they work for the administration and serve as its arms, legs, eyes, ears, and mouthpieces.

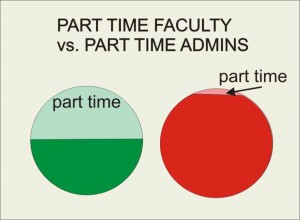

While some administrative posts continue to be held by senior professors on a part-time basis, their ranks are gradually dwindling as their jobs are taken over by fulltime managers. College administrations frequently tout the fiscal advantages of using part-time, “adjunct” faculty to teach courses. They fail, however, to apply the same logic to their own ranks.

Over the past thirty years, the percentage of faculty members who are hired on a part-time basis has increased so dramatically that today almost half of the nation’s professors work only part-time. And yet the percentage of administrators who are part-time employees has fallen during the same time period.

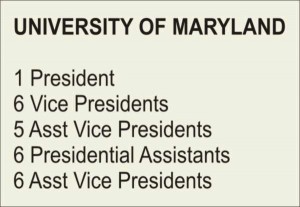

Administrators are not only well staffed, they are also well paid. Vice presidents at the University of Maryland, for example, earn well over $200,000, and deans earn nearly as much. Both groups saw their salaries increase as much as 50 percent between 1998 and 2003, a period of financial retrenchment and sharp tuition increases at the university. Administrative salaries are on the rise everywhere in the nation. By 2007, the median salary paid to the president of a doctoral degree-granting  institution was $325,000. Eighty-one presidents earned more than $500,000, and twelve earned over $1 million. Presidents, at least, might perform important services for their schools. Somewhat more difficult to explain is the fact that by 2010 even some of the ubiquitous and largely interchangeable deanlets and deanlings earned six-figure salaries.

institution was $325,000. Eighty-one presidents earned more than $500,000, and twelve earned over $1 million. Presidents, at least, might perform important services for their schools. Somewhat more difficult to explain is the fact that by 2010 even some of the ubiquitous and largely interchangeable deanlets and deanlings earned six-figure salaries.

If you have any remaining doubt about where colleges and universities have been spending their increasing tuition and other revenues, consider this: between 1947 and 1995 (the last year for which the relevant data was published), administrative costs increased from barely 9 percent to nearly 15 percent of college and university budgets. More recent data, though not strictly comparable, follows a similar pattern. During this same time period, stated in constant dollars, overall university spending increased 148 percent. Instructional spending increased only 128 percent, 20 points less than the overall rate of spending increase. Administrative spending, though, increased by a whopping 235 percent.

Three main explanations are often adduced for the sharp growth in the number of university administrators over the past thirty years. One is that there have been new sorts of demands for administrative services that require more managers per student or faculty member than was true in the past. Universities today have an elaborate IT infrastructure, enhanced student services, a more extensive fund-raising and lobbying apparatus, and so on, than was common thirty years ago. Of course, it might also be said that during this same time period, whole new fields of teaching and research opened in such areas as computer science, genetics, chemical biology, and physics. Other new research and teaching fields opened because of ongoing changes in the world economy and international order. And yet, faculty growth between 1975 and 2005 simply kept pace with growth in enrollments and substantially lagged behind administrative and staff growth. When push came to shove, colleges chose to invest in management rather than in teaching and research.

A second common explanation given for the expansion of administration in recent years is the growing need to respond to mandates and record-keeping demands from federal and state governments as well as numerous licensure and accreditation bodies. It is certainly true that large numbers of administrators spend a good deal of time preparing reports and collecting data for these and other agencies. But as burdensome as this paperwork blizzard might be, it is not clear that it explains the growth in administrative personnel that we have observed. Often, affirmative action reporting is cited as the most time consuming of the various governmental mandates. As the economist Barbara Bergmann has pointed out, however, across the nation only a handful of administrators and staffers are employed in this endeavor.

More generally, we would expect that if administrative growth were mainly a response to external mandates, growth should be greater at state schools, which are more exposed to government obligations, than at private institutions, which are freer to manage their own affairs in their own way. Yet, when we examine the data, precisely the opposite seems to be the case. Between 1975 and 2005, the number of administrators and managers employed by public institutions increased by 66 percent. During the same time period, the number of administrators employed by private colleges and universities grew by 135 percent (see Table 4). These numbers seem inconsistent with the idea that external mandates have been the forces driving administrative growth at America’s institutions of higher education.

A third explanation has to do with the conduct of the faculty. Many faculty members, it is often said, regard administrative activities as obnoxious chores and are content to allow these to be undertaken by others. While there is some truth to this, it is certainly not the whole story. Often enough, I have observed that professors who are willing to perform administrative tasks lose interest when they find that the committees, councils, and assemblies through which the faculty nominally acts have lost much if not all their power to administrators.

If growth-driven demand, governmental mandates, and faculty preferences are not sufficient explanations for administrative expansion, an alternative explanation might be found in the nature of university bureaucracies themselves. In particular, administrative growth may be seen primarily as a result of efforts by administrators to aggrandize their own roles in academic life. Students of bureaucracy have frequently observed that administrators have a strong incentive to maximize the power and prestige of whatever office they hold by working to increase its staff and budget. To justify such increases, they often seek to capture functions currently performed by others or invent new functions for themselves that might or might not further the organization’s main mission.

With fewer deanlets to command, senior administrators would be compelled to turn once again to the faculty for administrative support. Such a change would result in better programs and less unchecked power for presidents and provosts. Faculty who work part-time or for part of their careers as administrators tend to ask questions, use judgment, and interfere with arbitrary presidential and provostial decision making. Senior full-time administrators might resent the interference, but the university would benefit from the result. Moreover, with fewer administrators to pay and send to conferences and retreats, more resources might be available for educational programs and student support, the actual items for which parents, donors, and funding agencies think they are paying.

Such behavior is common on today’s campuses. At one school, an inventive group of administrators created the “Committee on Traditions,” whose mission seemed to be the identification and restoration of forgotten university traditions or, failing that, the creation of new traditions. Another group of deans constituted themselves as the “War Zones Task Force.” This group recruited staffers, held many meetings, and prepared a number of reports whose upshot seemed to be that students should be discouraged from traveling to war zones, unless, of course, their home was in a war zone. But perhaps the expansion of university bureaucracies is best illustrated by an ad placed by a Colorado school, which sought a “Coordinator of College Liaisons.” Depending on how you read it, this is either a ridiculous example of bureaucratic layering or an intrusion into an area of student life that hardly requires administrative assistance. ….For example, at a recent “president’s staff meeting” at an Ohio community college, eleven of the eighteen agenda items discussed by administrators involved plans for future meetings or discussions of other recently held meetings. At a gathering of the “Process Management Steering Committee” of a Midwestern community college, virtually the entire meeting was devoted to planning subsequent meetings by process management teams, including the “search committee training team,” the “faculty advising and mentoring team,” and the “culture team,” which was said ……..

read the full essay, without my editing,

That still leaves us with the question of why we have become less efficient in an era where the rest of American intellectual enterprise has become MORE efficient. Ginsberg’s answer is simple . He suggests that there is no competitive pressure on university administrations to control their costs.

Let me give you two examples:

1. Compliance., Why does it matter if some of that cost is explained by the need for compliance? What are the forces that drive decisions about compliance? Does the Provost decide her salary or the size of her staff must be cut in order to hire more attorneys? Ginsberg argues that the answer to this is no.

2. Research overhead. Who determines how much overhead we get from NIH? Sadly the scientific community is excluded from that process. Even though we are required to sign off on grants, to accept responsibility for how money is spent, there is no accountability by the administration to the investigators,

They, the folks who pay for this place, want us to be price competitive. Ginsberg suggests that the faculty are price competitive because it is in our interest to be so. He argues that we need to return to the time when administration was a faculty responsibility and administrators worked for us, To the student or legislator paying tuition, or the taxpayer funding NIH, it does not matter whether administrators are using their money to pay themselves or increase their staffs; the difference is a distinction with no meaning.

Ginsberg suggests that the answer in academia is to return the faculty to its traditional role in governing the university